Abstract

The effects of antidepressants on the gastrointestinal tract may contribute to their potential efficacy in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome; buspirone, a prototype 5-HT1A agonist, enhances gastric accommodation and reduces postprandial symptoms in response to a challenge meal. Paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, accelerates small bowel but not colonic transit, and this property may not be relevant to improve gut function in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Venlafaxine, a prototype serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, enhances gastric accommodation, increases colonic compliance and reduces sensations to distension; however, it is associated with adverse effects that reduce its applicability in treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants reduce sensations in response to food, including nausea, and delay gastric emptying, especially in females. Buspirone appears efficacious in functional dyspepsia; amitriptyline was not efficacious in a large trial of children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clinical trials of antidepressants for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome are generally small. The recommendations of efficacy and number needed to treat from meta-analyses are suspect, and more prospective trials are needed in patients without diagnosed psychiatric diseases. Antidepressants appear to be more effective in the treatment of patients with anxiety or depression, but larger prospective trials assessing both clinical and pharmacodynamic effects on gut sensorimotor function are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

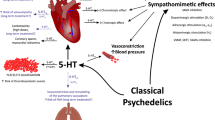

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a multifactorial disorder in which psychosocial aspects interact with altered functioning to cause a disorder with high clinical and societal impact. A pivotal neurotransmitter mediating central and peripheral dysfunction is serotonin (5-HT). Serotonin is an important neurotransmitter in both the brain and gastrointestinal tract, where it plays a key role in the regulation of sensory and motor functions.

Serotonergic receptors and the reuptake of serotonin modify the effects of the neurotransmitter. This is exemplified by the variation in the reuptake of serotonin through genetic variations in the uptake process. 5-HT transporter (SERT, also called SLC6A4) is central to fine-tuning brain 5-HT neurotransmission and is abundant in cortical and limbic areas, thereby affecting emotional aspects of behavior, the occurrence of anxiety, and other psychiatric disease. Variation in the promoter region upstream of the 5-HT coding sequence (SERT-P) or promoter is manifest as long polymorphic region (5HTTLPR) and short variants of the region impact the response to antidepressant treatment [1]. In addition, 5-HTTLPR genotype (s allele) is associated with higher pain sensory ratings during rectal distension in health and IBS [2], and 5-HTTLPR (s/s genotype) activates greater regional cerebral blood flow in specific brain regions (left anterior cingulate cortex and right parahippocampal gyrus) in response to 0–40 mmHg colorectal distention in humans [3].

Serotonergic psychoactive agents are frequently used in treatment of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). The central effects of these agents are well established; however, there are also gastrointestinal effects of these agents. The objectives of this paper are to review the pharmacodynamic effects of these agents on gastrointestinal functions, and to examine how these effects might be reflected in results of randomized, controlled trials with these agents.

Serotonergic psychoactive agents and pharmacodynamics in functional dyspepsia

The Rome III criteria for functional dyspepsia are as follows [4].

Patients must have had one or more of the following symptoms for the past 3 months, with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis: postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric burning, as well as no evidence of structural disease that is likely to explain symptoms (including any condition detected by upper endoscopy). This is further classified as:

-

(A)

Postprandial distress syndrome

-

(B)

Epigastric pain syndrome

In general, the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia involves psychosocial factors, altered motility (including gastric emptying and accommodation) and altered sensation; a subset of patients reports a prior episode of gastroenteritis.

Among serotonergic psychoactive agents proposed for treatment of functional dyspepsia, buspirone, a 5-HT1A receptor agonist, enhanced gastric relaxation [5], and paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI, 30 mg paroxetine daily for 4 days), accelerated orocecal transit in 10 healthy controls and 8 IBS patients, but there was no effect on whole gut transit time [6, 7].

There is a third class of combined serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), of which a prototype is venlafaxine. In a detailed study of upper gastrointestinal functions (gastric emptying accommodation and satiation) in healthy participants [8], the effects of a spectrum of serotonergic psychoactive agents administered (at standard starting doses to treat anxiety and depression) for 11 days showed that paroxetine, 20 mg per day, accelerated orocecal transit of a solid meal; buspirone, 10 mg p.o. twice daily, decreased postprandial aggregate symptom and nausea scores after a fully satiating liquid nutrient meal; and venlafaxine-XR, 75 mg per day, enhanced gastric accommodation measured by SPECT imaging, a validated method to measure gastric volume [9, 10]. These data suggest a potential for use of buspirone and venlafaxine in functional dyspepsia.

Has this been translated into efficacious treatment in patients with functional dyspepsia? Tack et al. examined the effects of buspirone on gastric functions and postprandial symptoms in 17 patients with functional dyspepsia in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. The study showed reduction in fullness, bloating, belching, and nausea, as well as overall dyspepsia severity score, and this was associated with increased postprandial accommodation, but there were no significant effects on gastric emptying or sensation thresholds in response to balloon distension in the stomach [11].

On the other hand, the effects of venlafaxine, 75–150 mg, compared to placebo were tested in functional dyspepsia, but this treatment was associated with considerable drop-outs secondary to adverse events (such as nausea, palpitations, sweating, sleeping disorders, dizziness, visual impairment), and no overall clinical efficacy was demonstrated during treatment or follow-up [12].

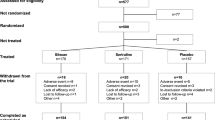

The effects of the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), amitriptyline, on postprandial symptoms were tested in healthy volunteers and in patients with functional dyspepsia. In healthy volunteers, amitriptyline retards gastric emptying and reduces postprandial (caloric drink challenge) symptoms, especially nausea [13]. A single-center, parallel-group study showed amitriptyline (12.5–50 mg for 8 weeks), compared to placebo, did not affect drinking capacity and postprandial symptoms evoked by the drink test in 38 functional dyspepsia patients. However, during the entire treatment, nausea symptom score was significantly reduced by amitriptyline compared with placebo [14]. Results of an NIH-funded multicenter study of clinical efficacy are awaited [15]. Meanwhile, a small study from Japan compared amitriptyline to no treatment in patients with functional dyspepsia who were famotidine and mosapride non-responders. Significant benefits were observed in the amitriptyline groups [16]. On the other hand, a large multicenter study of amitriptyline in children with diverse FGIDs showed no benefit of the TCA over placebo [17].

Serotonergic psychoactive agents and pharmacodynamics in irritable bowel syndrome

The Rome III diagnostic criteria for IBS [18] are as follows:

Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month in the last 3 months associated with 2 or more of the following:

-

1.

Improvement with defecation

-

2.

Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

-

3.

Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

In general, the pathophysiology of IBS involves psychosocial factors, altered motor function (including motility and transit), altered sensation, and altered host genetic and intraluminal factor interactions [19, 20]. Many patients report a prior episode of gastroenteritis.

In a detailed study of lower gastrointestinal functions (colonic motility, compliance and sensation) in healthy participants [21], buspirone had virtually no effects, whereas venlafaxine increased compliance, relaxed tone, reduced postprandial colonic contraction, and tended to increase thresholds for sensation of first perception and gas, while it also reduced pain sensation ratings in response to grades distensions. Both buspirone and venlafaxine did not significantly alter colonic transit in healthy participants [8].

The main effect of the SSRI, fluoxetine (20 mg a day for 6 weeks), was to reduce pain scores, especially in non-depressed IBS patients who were hypersensitive at baseline before drug administration, but no differences were seen in rectal sensation in the overall group [22].

Another SSRI, citalopram, was tested first in healthy volunteers. Acute citalopram infusion increased colonic contractility, including induction of high amplitude propagated contractions, reduced colonic tone during fasting, as well as reduced the increase in tone after meal ingestion. While citalopram increased colonic compliance, it had no significant effect on sensation [23]. In a separate, small cross-over, randomized, controlled trial of 23 patients with IBS, Tack et al. [24] showed efficacy of citalopram in pain, bloating and overall symptom scores. These effects were independent of anxiety, depression, and colonic sensorimotor function. On the other hand, in a slightly smaller study, Talley et al. [25] showed no benefit with citalopram on global IBS endpoints over placebo. In a large, multicenter, parallel- group, randomized, controlled trial, both paroxetine and psychotherapy improved health-related quality of life in severe IBS without any additional costs [26]. In another placebo controlled trial of IBS patients, refractory to high-fiber diet, paroxetine improved overall well-being, but no improvement was seen in abdominal pain, bloating, or social functioning [27]. Another small study examining effects of fluoxetine in Rome II IBS-C patients showed decrease in abdominal discomfort, bloating, and improvements in stool frequency and consistency [28]. No study has examined the efficacy of mirtazapine in symptoms or sensorimotor function in IBS.

An interesting animal study highlights difficulty in correlating antinociceptive effects of drugs with different antidepressant classes across a range of neuropathic pain models, and suggests that antidepressants with both noradrenaline and 5-HT action might have more potent antinociceptive effects than SSRIs [29].

Efficacy of serotonergic psychoactive agents in meta-analyses in irritable bowel syndrome

The American College of Gastroenterology Task Force Report of 2009 suggested there are several effective treatments for IBS, such as fiber, peppermint oil, antidepressants, probiotics, and antispasmodics/smooth muscle relaxants. Indeed, the estimated number needed to treat was as low as 4 for many classes of treatment, including antidepressants [30]. Other meta-analyses reached different conclusions. There is always concern when meta-analyses include trials with different designs, different doses, diverse mechanisms, and small trials to reach conclusions that are often proposed in societal guidelines. It is wise to follow the counsel that meta-analyses should only be used for hypothesis generation [31]. Moreover, when multiple treatment comparison meta-analyses use indirect evidence from randomized controlled trials to compare the relative effectiveness of all included interventions, they are particularly vulnerable to potential biases that can affect the interpretation of these analyses [32]. In fact, several systematic analyses have been published and reach different conclusions, and it is not surprising when one considers the different data sets that are included within each meta-analysis, whether they are commissioned by national societies [33], individual research groups [34], or the Cochrane Systematic reviews [35]. These illustrate different conclusions on the efficacy of antidepressants in IBS treatment.

Three specific studies included in many of these meta-analyses illustrate the dangers of these analyses based on the unrepresentative nature of the results, or the use of secondary endpoints in individual trials that are used in drawing conclusions of class effects when the primary endpoints are not significant. For example, in a trial of fluoxetine (an SSRI) in constipation-predominant IBS, there was an unrepresentative 10 % placebo response for discomfort and bloating [28], and, in a trial of 50 patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS, amitriptyline, 10 mg, was uncharacteristically efficacious, since 68 % of patients receiving this relatively low dose of amitriptyline showed complete response defined as loss of all symptoms, compared with only 28 % of those receiving placebo [36]. In a third study of flexible dose of paroxetine, there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint, that is, the reduction of composite pain scores [37]. On the other hand, meta-analyses often include the significant effects on clinical global impression scores to illustrate efficacy relative to placebo.

Moreover, the meta-analyses of antidepressants involve relatively small total patient numbers. For example, one meta-analysis [38] involved 13 studies that compared antidepressants to placebo for treatment of IBS with a total of 789 patients, 432 active therapy and 357 placebo. Several analyses showed heterogeneity and even publication bias with Funnel plot asymmetry, thus raising important flags that it is essential to cautiously interpret the results of meta-analyses.

Regrettably, there are few trials involving patients with IBS who were concomitantly suffering affective disorders [39]. In those settings, including anxiety [40] and depression [39], psychoactive agents may be more effective. Thus, in the systematic review of antidepressant agents in patients with IBS and comorbid depression, there were 4 studies of SSRIs, 4 of TCAs, 1 of SSRI vs. TCA, and 1 of a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (duloxetine) [41]. It is important to note that most studies excluded patients with diagnosed depression and/or anxiety, and that none of the controlled studies used the primary outcome of assessment of the symptoms of manic-depressive disorder in the IBS patients. The two SSRI studies (citalopram and paroxetine) reported a statistically significant, ~50 %, improvement in IBS symptoms [24, 27]. Paroxetine also provided an ~30 % improvement in scores on Beck Depression Inventory (also statistically significant) [27]. Of two studies of fluoxetine, one (reviewed above) showed benefit on IBS symptoms, though the 10 % response to placebo for both pain and bloating seems uncharacteristically low. TCAs benefit IBS symptoms, predominantly diarrhea, as expected. In addition, one of the TCA studies found a significant improvement in depressive symptoms with desipramine, 150 mg/day, (p = 0.025) [42].

Summary and conclusions

In conclusion, the effects of antidepressants on the gastrointestinal tract may contribute to their potential efficacy in functional dyspepsia and IBS; buspirone appears efficacious in functional dyspepsia. Clinical trials of antidepressants for treatment of IBS are generally small. The recommendations of efficacy and number needed to treat from meta-analyses are suspect, and more prospective trials are needed. Additionally, novel mechanisms such as effects on gut permeability and immune dysregulation in IBS need to be explored.

References

Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–31.

Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Carlson P, McKinzie S, Burton D, Baxter K, Ryks M, Zinsmeister AR. Candidate genes and sensory functions in health and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:G219–25.

Fukudo S, Kanazawa M, Mizuno T, Hamaguchi T, Kano M, Watanabe S, et al. Impact of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism on brain activation by colorectal distention. Neuroimage. 2009;47:946–51.

Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–79.

van Oudenhove L, Kindt S, Vos R, Coulie B, Tack J. Influence of buspirone on gastric sensorimotor function in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1326–33.

Gorard DA, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and human small intestinal motility: effect of inhibiting 5-hydroxytryptamine reuptake. Gut. 1994;35:496–500.

Gorard DA, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. Influence of antidepressants on whole gut and orocaecal transit times in health and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:159–66.

Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Burton D, Thomforde G, Olden KW, Stephens D. Selective effects of serotonergic psychoactive agents on gastrointestinal functions in health. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:G130–7.

Bouras EP, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Castillo EJ, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, et al. SPECT imaging of the stomach: comparison with barostat and effects of sex, age, body mass index, and fundoplication. Gut. 2002;51:781–6.

Breen M, Camilleri M, Burton D, Zinsmeister AR. Performance characteristics of the measurement of gastric volume using single photon emission computed tomography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:308–15.

Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, Farré R, Van Oudenhove L. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1239–45.

van Kerkhoven LA, Laheij RJ, Aparicio N, De Boer WA, Van den Hazel S, Tan AC, et al. Effect of the antidepressant venlafaxine in functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:746–52.

Bouras EP, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Heckman MG, Crook JE, et al. Effects of amitriptyline on gastric sensorimotor function and postprandial symptoms in healthy individuals: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2043–50.

Braak B, Klooker TK, Wouters MM, Lei A, van den Wijngaard RM, Boeckxstaens GE. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of amitriptyline on drinking capacity and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:638–48.

Talley NJ, Locke GR 3rd, Herrick LM, Silvernail VM, Prather CM, Lacy BE, et al. Functional Dyspepsia Treatment Trial (FDTT): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants in functional dyspepsia, evaluating symptoms, psychopathology, pathophysiology and pharmacogenetics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:523–33.

Otaka M, Jin M, Odashima M, Matsuhashi T, Wada I, Horikawa Y, et al. New strategy of therapy for functional dyspepsia using famotidine, mosapride and amitriptyline. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(Suppl 2):42–6.

Saps M, Youssef N, Miranda A, Nurko S, Hyman P, Cocjin J, et al. Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1261–9.

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91.

Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1626–35.

Camilleri M. Mechanisms in IBS: something old, something new, something borrowed…. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:311–6.

Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Ferber I, Delgado-Aros S, Burton D, McKinzie S, et al. Effects of venlafaxine, buspirone and placebo on colonic sensorimotor functions in healthy humans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:211–8.

Kuiken SD, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine does not change rectal sensitivity and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:219–28.

Tack J, Broekaert D, Corsetti M, Fischler B, Janssens J. Influence of acute serotonin reuptake inhibition on colonic sensorimotor function in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:265–74.

Tack J, Broekaert D, Fischler B, Van Oudenhove L, Gevers AM, Janssens J. A controlled crossover study of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:1095–103.

Talley NJ, Kellow JE, Boyce P, Tennant C, Huskic S, Jones M. Antidepressant therapy (imipramine and citalopram) for irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:108–15.

Creed F, Fernandes L, Guthrie E, Palmer S, Ratcliffe J, Read N, Rigby C, Thompson D, Tomenson B, North of England IBS Research Group. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:303–17.

Tabas G, Beaves M, Wang J, Friday P, Mardini H, Arnold G. Paroxetine to treat irritable bowel syndrome not responding to high-fiber diet: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:914–20.

Vahedi H, Merat S, Rashidioon A, Ghoddoosi A, Malekzadeh R. The effect of fluoxetine in patients with pain and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind randomized-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:381–5.

Bomholt SF, Mikkelsen JD, Blackburn-Munro G. Antinociceptive effects of the antidepressants amitriptyline, duloxetine, mirtazapine and citalopram in animal models of acute, persistent and neuropathic pain. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:252–63.

Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence-based systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;10:S1–35.

Hennekens CH, Demets D. The need for large-scale randomized evidence without undue emphasis on small trials, meta-analyses, or subgroup analyses. JAMA. 2009;302:2361–2.

Mills EJ, Ioannidis JP, Thorlund K, Schünemann HJ, Puhan MA, Guyatt GH. How to use an article reporting a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308:1246–53.

Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367–78.

Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. Efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1548–53.

Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD003460.

Vahedi H, Merat S, Momtahen S, Kazzazi AS, Ghaffari N, Olfati G, et al. Clinical trial: the effect of amitriptyline in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:678–84.

Masand PS, Pae CU, Krulewicz S, Peindl K, Mannelli P, Varia IM, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine controlled-release in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:78–86.

Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367–78.

Friedrich M, Grady SE, Wall GC. Effects of antidepressants in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and comorbid depression. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1221–33.

Masand PS, Gupta S, Schwartz TL, Kaplan D, Virk S, Hameed A, et al. Does a preexisting anxiety disorder predict response to paroxetine in irritable bowel syndrome? Psychosomatics. 2002;43:451–5.

Friedrich M, Grady SE, Wall GC. Effects of antidepressants in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and comorbid depression. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1221–33.

Drossman, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19–31.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Cindy Stanislav for excellent secretarial assistance. No relevant disclosures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grover, M., Camilleri, M. Effects on gastrointestinal functions and symptoms of serotonergic psychoactive agents used in functional gastrointestinal diseases. J Gastroenterol 48, 177–181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-012-0726-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-012-0726-5