Abstract

Objective

To investigate differences in healthcare cost trends over 8 years in adults with diabetes and one of four categories of comorbid depression: no depression, unrecognized depression, asymptomatic depression, or symptomatic depression.

Research Design and Methods

Data from the 2004–2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) was used to create nationally representative estimates. The dependent variable was total healthcare expenditures for the calendar year, including office-based, hospital outpatient, emergency room, inpatient hospital, prescription, dental, and home health care expenditures. The 2004–2011 direct medical costs were adjusted to a common 2014 dollar value. The primary independent variable was four mutually exclusive depression categories created from ICD-9-CM codes and the PHQ-2 depression screening tool. Healthcare expenditures were estimated using a two-part model and were adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, education, health insurance, metropolitan statistical area status, region, income level, and comorbidities.

Results

Based on a national sample of adults with diabetes (unweighted sample of 15,548, weighted sample of 17,465,579), 10.2 % had unrecognized depression, 13.6 % had asymptomatic depression, and 8.9 % had symptomatic depression. In the pooled sample, after adjusting for covariates, the incremental cost of unrecognized depression was $2872 (95 % CI 1660–4084), asymptomatic depression increased by $3347 (95 % CI 2568–4386), and symptomatic depression increased by $5170 (CI 95 % 3610–6731) compared to patients with no depression.

Conclusions

Adjusted analyses showed that expenditures were $2000–3000 higher for unrecognized and asymptomatic depression than no depression, and $5000 higher for symptomatic depression. Higher medical expenditures persisted over time, with only symptomatic depression showing a sustained decrease over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The coexistence of depression and diabetes is associated with increased mortality and morbidity, including higher rates of complications, increased disability and lost productivity, lower quality of life, and increased risk of death.1 Compounding this impact is the high prevalence of diabetes and depression, with a meta-analysis showing major depression occurring in 11 % of individuals with diabetes and clinically relevant depression in 31 %.2 In addition, 45 % of diabetes patients are estimated to have undiagnosed depression,3 and patients with diabetes are more likely to be diagnosed with depression than those without diabetes,4 suggesting that the influence of depression on the outcomes of patients with diabetes may be greater than prevalence numbers alone suggest.

Major depression and depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes are also consistently associated with decreased income, increased healthcare utilization, and higher healthcare costs.1,5 Studies have shown that healthcare expenditures for patients with diabetes and depression are 2 to 4.5 times as high as those of patients without depression.6,7 Differences between those with and without depression include higher diabetes-related costs, more time at inpatient facilities, more ambulatory care visits, and more prescriptions.8–10 Patients with diabetes and "probable depression" have also shown increased healthcare costs compared to patients without depression,11 and a study of depression symptom severity found that healthcare costs increased as the severity of depressive symptoms increased.7

These costs are even more important when considered at a population level, given the high prevalence and expense of diabetes to the US population.12 Though the recognition and treatment of depression for patients with diabetes is consistently recommended, it is less than optimal.13 Studies show that only 50 % of diabetes patients with depression are recognized in primary care settings, and diagnosis does not change treatment patterns.13 One study examined the effects of implementing a depression intervention for diabetes patients in nine primary care practices, and found a 5-year mean total cost reduction of $3907 for patients who received the intervention compared with patients receiving usual care.14 A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of psychological interventions to treat depression in patients with diabetes also found net savings, though few such studies existed.15

While research has consistently shown increased costs of depression in patients with diabetes, we are not aware of any studies investigating national estimates of costs for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, or studies providing trends over time for these costs. The present study used the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) to investigate the impact of depression on healthcare costs in a nationally representative sample of patients with diabetes. Patients were categorized as having no depression, unrecognized depression based on a validated depression screening questionnaire, asymptomatic depression, or symptomatic depression. This is the first study of its kind, and it adds significantly to the literature by considering the healthcare cost differences between patients with these four categories of depression over a period of 8 years, using a novel cost methodology to provide national estimates.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

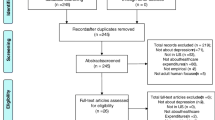

The study used data from the 2004–2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to estimate the cost of depression among adults with diabetes (aged ≥18 years).

Data

MEPS provides nationally representative estimates of healthcare use and expenditure, and is maintained and co-sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).16,17 It collects detailed information on individual sociodemographic characteristics, health conditions, healthcare use and expenditures, sources of payment, and health insurance coverage.16 MEPS has three components: Household Component (HC), Medical Provider Component (MPC), and Insurance Component (IC).16,17 Information on the HC is collected by self-reports, and the MPC requests data on medical and financial characteristics from hospitals, physicians, home healthcare providers, and pharmacies in order to validate and supplement information received from the MEPS-HC respondents.16,18 Diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) are also collected as part of the MPC.

The panel design of the MEPS survey includes five rounds of interviews covering two full calendar years.16 Each panel collects data from different individuals, so merging of panel data creates a pooled cross-sectional sample. We used 8 years of MEPS data to create a pooled sample as follows: 2004/2005, 2006/2007, 2008/2009, and 2010/2011. Adults with diabetes were included based on patient self-reports. MEPS does not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5 % of diagnosed cases are type 1 diabetes and 90–95 % of diagnosed cases are type 2 diabetes.12

For each year, we merged data for adults with diabetes from the household survey of the medical condition files and full-year consolidated files using the unique person identifier on a one-to-one match.18 The pooled sample has a common variance structure necessary to ensure compatibility and comparability of variables within the complex sample design.19 Analytic sampling weight variables were adjusted by dividing by the number of years pooled. The sum of these adjusted weights represented the average annual population size for the pooled period, and reflected an “average annual” basis rather than the entire pooled period.20 As a result, analyses account for the sampling weights, clustering, and stratification design to estimate the nationally representative aggregate and incremental healthcare expenditure for the US population.16,17

Medical Expenditures

The dependent variable was the direct cost calculated as total healthcare expenditures for the calendar year of each observation. More specifically, in MEPS, an expenditure is defined as the sum of direct payments for care provided during the year, including out-of-pocket payments and payments by private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, and other sources.16 The total medical expenditure comprises office-based medical provider, hospital outpatient, emergency room, inpatient hospital (including zero night stays), prescription medicine, dental, home healthcare, and other medical expenditures.16 The 2004–2011 direct medical costs were adjusted to a common 2014 dollar value using the Consumer Price Index provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl).

Depression

The primary independent variable was four mutually exclusive depression categories created from ICD-9-CM codes and the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) depression screening tool. Previously validated ICD-9-CM codes 296, 300, 309, and 311 associated with at least one office-based medical provider, hospital outpatient, or emergency room visit, inpatient hospital stay, or prescription medication were used to identify individuals with clinical depression.21,22 Responses to the PHQ-2 were used to identify depression symptoms. The PHQ-2 is a two-question self-report scale included in the MEPS questionnaire. It was designed to inquire about an individual's depressed mood over the prior 2 weeks by asking questions about whether the respondent had little interest or pleasure or felt down/depressed/hopeless. Answer options for each range from 0 to 3, with total scores of 0 to 6 representing a summation of the values, and higher values indicating a greater tendency towards depression.23 The PHQ-2 using a cutpoint of ≥3 has sensitivity of 83 % and specificity of 92 % for identifying major depression, and is often used for screening of depressive symptoms.23 The scale was developed to indicate the probability of depression, and is not intended to measure severity or to represent a diagnosis of depression. As such, in this analysis it is used as an indicator of the presence or absence of symptoms as measured by the scale. Two dummy variables were created for each patient using the ICD-9 diagnosis and PHQ-2 cutpoint of ≥3, below which the number of symptoms as measured by the scale indicated a low probability of currently screening for depression.

ICD-9 and PHQ-2 measures for the same calendar year were used to create four categories:

-

1.

No depression, defined as individuals with neither depressive symptoms as determined by the PHQ-2 nor ICD-9 diagnosis of depression;

-

2.

Unrecognized depression, defined as individuals with PHQ-2 depressive symptoms but without ICD-9 diagnosis of depression;

-

3.

Asymptomatic depression, defined as individuals with ICD-9 diagnosis of depression (diagnostic codes 296, 300, 309, 311) but without PHQ-2 depressive symptoms; and

-

4.

Symptomatic depression, defined as individuals with both PHQ-2 depressive symptoms and clinical depression by ICD-9 diagnosis (codes 296, 300, 309, 311).

Categories do not represent severity of depression, but rather the presence or absence of a diagnosis (as defined by the ICD-9 codes) and/or the presence or absence of symptoms (as defined by the PHQ-2 scale).

Covariates

Adjusted analyses used covariates collected through self-reports. Covariates were selected based on the literature to include variables that account for possible variation in medical expenditures or that address disease burden. Binary indicators of comorbidities were based on responses to a series of questions asking whether respondents had ever been diagnosed with specific diseases. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) thus indicates a positive response to diagnosis with coronary heart disease, angina, myocardial infarction, or other heart diseases. Race/ethnicity, age, education, health insurance, and marital status were each divided into three categories (see Table 1). Census region and metropolitan statistical area (MSA) were based on residence as of the end of the year. Income was defined as a percentage of the poverty level and was grouped into four categories.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to determine sociodemographic and comorbidity variables across the four depression categories among adults with diabetes over the 8-year pooled dataset. Unadjusted mean and standard pairwise comparisons were used to compare the total healthcare expenditures by depression categories.24 Mean expenditures between the six paired groups were compared by sociodemographic and comorbidity variables as well as by year.

Adjusted healthcare expenditures were estimated using a two-part model.25,26 In the two-part model, a probit model was estimated for the probability of observing a zero versus positive medical expenditure. Positive medical expenditure is defined as any healthcare expenditure greater than zero.26 Conditional on having a positive medical expenditure, a generalized linear model (GLM) was estimated.27,28 GLM was used instead of log OLS [ordinary least squares] regression, since it relaxes the normality and homoscedasticity assumptions and avoids bias associated with re-transforming to the raw scale.27 The results of the modified Park test verified that the use of a gamma distribution with a log link was the best–fitting GLM for consistent estimation of coefficients and marginal effects of medical expenditures.28,29 Multicollinearity was checked for predictors of the two-part model, taking into account the complex survey design. The variance inflation factor (VIF) for all predictors used in the two-part model indicated no multicollinearity problems. The F-test for the two-part regression models was found to be significant, which indicated the overall significance of the regression model.

Two-part models have been widely employed in situations where, due to a large number of non-users of health services, there are excess zeros in the resource use or cost data, and the assumption of normality of the error term is not satisfied.30 Marginal effects were then estimated from the combined first and second parts of the final model.27 To control for confounding, sociodemographic factors including age, sex, race, marital status, education, health insurance, metropolitan statistical area status, region, income level, and comorbidities were included in the fully adjusted model. All analyses were performed at the individual level using STATA 13 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance of p < 0.05 was used.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

The resulting dataset was an unweighted sample of 15,548 adults with diabetes (weighted sample of 17,465,579). Among the adults with diabetes in the pooled sample, 10,473 (67.3 %) individuals had no depression, 1579 (10.2 %) had unrecognized depression, 2117 (13.6 %) had asymptomatic depression, and 1379 (8.9 %) had symptomatic depression. Demographic characteristics overall and by depression category are shown in Table 1. Unrecognized depression was more likely in the 65–85 age group, minorities, those with less than high school education, and low-income individuals.

Unadjusted Cost Differences for Depression Categories Across Years

The results of unadjusted mean medical expenditures attributable to the four depression categories over time are shown in Table 2. The overall mean medical expenditures for patients with diabetes were $10,016 (95 % CI 9589–10,442) for those with no depression, $15,155 (95 % CI 13,587–16,723) for those with unrecognized depression, $16,134 (95 % CI 14,885–17,382) for those with asymptomatic depression, and $20,105 (95 % CI 18,103–22,106) for patients with symptomatic depression. Pairwise comparison tests showed significant differences in mean expenditures between all paired groups except those between asymptomatic and unrecognized depression.

Figure 1 shows the mean expenditures per person per year by the four depression categories. The no-depression category showed little change across the years, and remained the lowest of the four categories. Symptomatic depression showed a decrease over time, but a higher sustained cost than any of the other categories. Unrecognized and asymptomatic depression showed decreases from 2004/2005 to 2006/2007, but gradual increases towards 2010/2011.

Figure 2 shows the mean expenditures per person per year by the four depression categories broken down by total, inpatient, outpatient, prescription, office-based, and emergency room costs. No depression was consistently the lowest cost category, and symptomatic depression the highest in all cost types. Unrecognized depression showed costs similar to but lower than asymptomatic depression, with the exception of inpatient and outpatient costs. The two highest cost types were inpatient and prescription costs.

Adjusted Incremental Cost Differences for Depression Categories Among Diabetes

The results of the adjusted two-part GLM on the incremental costs associated with the four depression categories, sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, and time trends are shown in Table 3. In the pooled sample, after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, and time trend covariates, the incremental cost of unrecognized depression increased by $2872 (95 % CI 1660–4084), asymptomatic depression increased by $3347 (95 % CI 2568–4386), and symptomatic depression increased by $5170 (CI 95 % 3610–6731) compared to patients with no depression.

Estimated US Burden of Depression Among Adults With Diabetes

Finally, we estimated the aggregate cost during the period 2004–2011 among adults with diabetes. Based on the unadjusted mean, the average annual aggregate costs for the US population with diabetes were estimated at $21.3 billion for unrecognized depression, $42.9 billion for asymptomatic depression, and $30.3 billion for symptomatic depression. The adjusted total incremental costs increased by $4.0 billion for unrecognized depression, $9.2 billion for asymptomatic depression, and $7.8 billion for symptomatic depression, compared to those with no depression.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on a national sample of adults with diabetes, mean medical expenditures were $5000–6000 higher for those with unrecognized and asymptomatic depression than with no depression, and twice as high for those with symptomatic depression. Unrecognized depression showed higher expenditures than asymptomatic depression for inpatient and outpatient costs, while asymptomatic depression showed higher prescription and office-based costs than unrecognized depression. Adjusted analyses revealed that expenditures were still $2000–3000 higher for unrecognized and asymptomatic depression than for no depression, and $5000 higher for symptomatic depression. These higher medical expenditures persisted over time.

This study is the first of its kind, showing the impact of healthcare costs over time in patients with diabetes and different classifications of comorbid depression (unrecognized, asymptomatic, and symptomatic). The total economic burden of depression alone among the US population rose to an estimated $210.5 billion in 2010.31 Results of this study show the additional impact of unrecognized comorbid depression in patients with diabetes at the individual and national levels ($4 billion at the population level). Asymptomatic depression also costs significantly more than patients with no depression ($9 billion for the US population). This economic burden is important to consider given the high prevalence of depression in patients with diabetes, the epidemic of diabetes in the United States, and the persistent costs over time shown by this study. Estimates in this study show that depression is a costly comorbidity, with only CVD and stroke showing increased costs comparable to any of the depression categories for patients with diabetes. Recent work on diabetes alone and chronic kidney disease show that the costs for all individual comorbid depression categories are higher than those for diabetes alone ($2558 per year), but lower than the costs of chronic kidney disease ($8473 per year).32,33

These results support the call for improved recognition of depression through increased screening at the primary care provider level.1,13,34 Comorbid depression is associated with decreased adherence to treatment, possibly leading to poorer glycemic control, higher complication rates, and increased healthcare use and cost.1 A systematic review of depression treatment for individuals with diabetes found that interventions were cost-effective compared to usual care.35 Therefore, increased use of interventions to address depression in patients with diabetes may result in a reduction in costs over time for symptomatic patients, but may not be sufficient to remove symptom load. Unrecognized and asymptomatic depression costs individual patients nearly $3000 more per year, and are not as often considered in interventions. While collaborative care programs have been shown to be moderately cost-effective, the offset to costs has not been enormous.7,14,15,36 In addition, increased mental health visits for patients with diabetes and depression were effective in reducing inpatient costs, but the savings did not offset outpatient and pharmacy costs.37 Based on this study, some costs associated with asymptomatic depression are the result of receiving treatment (higher for prescription and office-based visits than unrecognized depression). While the benefit of treatment to individuals is worth the offsetting costs, providers and policymakers should strive to develop alternatives that allow for treatment but also provide savings to the system overall. Strategies are needed to focus interventions on identifying patients that are symptomatic and in need of more aggressive treatment, in addition to identifying patients with unrecognized depression—for example, co-located primary care and telemental health.37

This study is strengthened by the use of nationally representative data, a large sample size, and a novel cost methodology; however, some limitations do exist. As with all pooled cross-sectional data, this study cannot show causality. Diabetes prevalence was based on self-reports rather than medical diagnosis, although previous studies have acknowledged the reliability of self-reporting of diabetes.38,39 In addition, self-reported comorbidities may not include all relevant comorbidities, and may include those that are not medically diagnosed. Finally, the PHQ-2 is a screening tool for major depression and requires further assessment using a diagnostic interview. Nevertheless, it a validated screening method, and has shown high sensitivity and specificity for depression.

In conclusion, using a pooled dataset over 8 years, we found that unrecognized and asymptomatic depression in patients with diabetes each resulted in an average of $3000 higher costs per year compared to patients without depression. Higher medical expenditures persisted over time, with only symptomatic depression showing a sustained decrease.

References

Egede LE, Ellis C. Diabetes and depression: global perspectives. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(3):302–12.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–78.

Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Ahjuwalia IB, Pearson WS, Mokdad AH. Prevalence and correlates of undiagnosed depression among US adults with diabetes: the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;83:268–79.

Ali S, Stone M, Skinner TC, Robertso N, Davies M, Khunti K. The association between depression and health-related quality of life in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26(2):75–89.

Dismuke CE, Egede LE. Association between major depression, depressive symptoms and personal income in US adults with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(5):484–91.

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:464–70.

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms of adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–85.

Le TK, Able S, Lage MJ. Resource use among patients with diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, or diabetes with depression. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2006;4:18–26.

Finkenstein EA, Bray JW, Chen H, Larson MJ, Miller K, Tompkins C, Keme A, Manderscheid R. Prevalence and costs of major depression among elderly claimants with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(2):415–20.

Nichols L, Barton PL, Glazner J, Mccollum M. Diabetes, minor depression and health care utilization and expenditure: a retrospective database study. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2007;5:4–12.

Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Katon WJ, Fan M, Pincus HA, Hogan D, Taylor J. Healthcare costs associated with depression in medically ill fee-for-service Medicare participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;S7:506–10.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

Egede LE. Failure to recognize depression in primary care: issues and challenges. J Gen Int Med. 2007;22:701–3.

Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, Lin EHB, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(6):1–11.

Jeeva F, Dickens C, Coventry P, Bundy C, Davies L. Is treatment of depression cost-effective in people with diabetes? a systematic review of the economic evidence. Int J Tech Assess Health Care. 2013;384–91.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. 2011 Full year consolidated data file 2013, Available from http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data_files.jsp. Accessed 18 August 2014.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Methodology Report # 27, Sample design of the 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component 2013, Available from http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/mr27/mr27.pdf. Accessed 22 August 2014.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2011 Medical conditions 2013, Available from http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h146/h146doc.pdf Accessed 20 August 2014.

DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Wallace LS. Children’s receipt of health care services and family health insurance patterns. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:406–13.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). MEPS HC-036: 1996-2011 Pooled Linkage Variance Estimation File 2013 MEPS file, Available from http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h36/h36u11doc.shtml. Accessed 18 August 2014.

Egede LE, Lynch CP, Gebregziabher M, Hunt KJ, Echols C, Gilbert GE, Mauldin PD. Differential impact of longitudinal medication non-adherence on mortality by race/ethnicity among veterans with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;28(2):208–15.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92.

Azkaya G, Ercan I. Examining multiple comparison procedures according to error rate, power type and false discovery rate. J Modern Appl Stat Methods. 2012;11(2):348–60.

Cameroon AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics using Stata 2010. StataCorp LP revised edition College Station, Texas.

Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–94.

Belotti F, Deb P, Manning WG, Norton EC. twopm: two-part models. Stata J. 2015;15(1):3–20.

Barnett SBL, Nurmagambetov TA. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002–2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):145–52.

Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, Rascati KL. Identifying patent characteristics associated with high Schizophrenia-related direct medical costs in community-dwelling patents. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(6):468–77.

Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O’Hhagan, Thompson SG. Review of statistical methods for analyzing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 2011;20:897–916.

Greenberg PE, Fournier A, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–62.

Ozieh MN, Dismuke CE, Lynch CP, Egede LE. Medical care expenditures associated with chronic kidney disease in adults with diabetes: United States 2011. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109(1):185–190.

Ozieh MN, Bishu KG, Dismuke CE, Egede LE. Trends of healthcare expenditure in United States in adults with diabetes: 2002–2011. Diabetes Care 2015b. Available online, doi: 10.2337/dc15-0369.

Lee H, Chapap D, Kao C, Jones D, Kapustin J, Smith J, Krichten C, Donner T, Thomas SA, Friedmann E. Depression, quality of life, and glycemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:214–24.

Jeeva F, Dickens C, Coventry P. Is treatment of depression cost-effective in people with diabetes? a systematic review of the economic evidence. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(4):384–91.

Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Rutter C, Manning WG, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young BA. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:65–72.

Egede LE, Gebregziabher M, Zhao Y, Dismuke CE, Walker RJ, Hunt KE, Axon RN. Impact of mental health visits on healthcare cost in patients with diabetes and comorbid mental health disorders. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e103804–e103804.

Bush TL, Miller SR, Golden AL, Hale WE. Self-report and medical record report agreement of selected medical conditions in the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1980;79:1554–6.

Harlow SD, Linet MS. Agreement between questionnaire data and medical records: the evidence for accuracy of recall. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:233–48.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

LEE obtained funding for the study. LEE, KB, RJW, and CED designed the study and developed the analysis. KB and LEE acquired and analyzed the data. LEE, KB, RJW, and CED contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding Source

This study was supported by grant no. K24DK093699 from The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (PI: Leonard Egede).

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), or Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Egede, L.E., Walker, R.J., Bishu, K. et al. Trends in Costs of Depression in Adults with Diabetes in the United States: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2004–2011. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 615–622 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3650-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3650-1