Abstract

Background:

Although obesity is associated with structural changes in brain grey matter, findings have been inconsistent and the precise nature of these changes is unclear. Inconsistencies may partly be due to the use of different volumetric morphometry methods, and the inclusion of participants with comorbidities that exert independent effects on brain structure. The latter concern is particularly critical when sample sizes are modest. The purpose of the current study was to examine the relationship between cortical grey matter and body mass index (BMI), in healthy participants, excluding confounding comorbidities and using a large sample size.

Subjects:

A total of 202 self-reported healthy volunteers were studied using surface-based morphometry, which permits the measurement of cortical thickness, surface area and cortical folding, independent of each other.

Results:

Although increasing BMI was not associated with global cortical changes, a more precise, region-based analysis revealed significant thinning of the cortex in two areas: left lateral occipital cortex (LOC) and right ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). An analogous region-based analysis failed to find an association between BMI and regional surface area or folding. Participants’ age was also found to be negatively associated with cortical thickness of several brain regions; however, there was no overlap between the age- and BMI-related effects on cortical thinning.

Conclusions:

Our data suggest that the key effect of increasing BMI on cortical grey matter is a focal thinning in the left LOC and right vmPFC. Consistent implications of the latter region in reward valuation, and goal control of decision and action suggest a possible shift in these processes with increasing BMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At present, >1.3 billion people across the world are overweight and an additional 600 million are obese. Overweight and obesity are the leading risk factors for deaths globally, being associated with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.1Although these illnesses are known to have effects on the brain, there is now an increasing evidence that obesity itself is associated with altered brain structure, possibly mediated by physiological dysregulations, such as low-grade inflammation,2 which has been linked to brain atrophy.3 The relevance of obesity to brain structure and function is further emphasised by the finding that it is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly,4 and in younger adults and children, it is associated with poorer memory and executive function (reviewed in Smith et al.5).

A number of studies have assessed the relationship between body weight and brain structure, predominantly focusing on the grey matter volume (GMV; Supplementary Table 1). Strikingly, the findings have proven highly inconsistent whether one considers global or regional changes in GMV. Although several studies have reported decreased total GMV in obesity,6, 7, 8, 9 others have reported no reductions.10, 11 Although the majority of studies report decreases in grey matter in a number of regions,6, 8, 12, 13, 14 the precise localisation has varied widely and some studies have even reported increases in regional GMV in obese subjects.8, 9, 14, 15, 16 Such inconsistencies pose a major challenge, impeding progress in developing an understanding of the relationship between weight dysregulations and the brain.

There are a number of possible reasons for the inconsistencies. First, obesity is driven by complex environmental, behavioural, metabolic and genetic determinants. The obese phenotype as defined by body mass index (BMI) is a heterogeneous one, being the outcome of several possible causal paths. This is a limitation of the BMI-based phenotype not unique to this particular question, but such heterogeneity can lead to significant variability of findings, particularly when sample sizes are small. Second, as the aforementioned comorbidities have been independently linked to brain atrophy, they represent potential confounders whose effects are difficult to quantify and control for (for example, the effect of diabetic status on brain structure). The presence of such confounders can also lead to inconsistent findings, particularly if they are treated differently across studies.

The third reason relates to the methods used to examine brain structure. Different measures of morphometry are differentially sensitive and reflect different structural changes. Most studies so far have used voxel-based morphometry that produces a probabilistic measure of GMV. This measure is determined through a pipeline of magnetic resonance image transformation and warping without regard for anatomical features of the cortex. Moreover, it is a composite of cortical thickness and surface area, which though correlated, represent distinct biological aspects of the cortex, and have different genetic components.17 Here we sought to overcome this limitation using a surface-based morphometric method, allowing us to disambiguate these measures, and thus permit more precise biological interpretation.18

In short, despite the growing body of work demonstrating grey matter changes associated with obesity, the precise nature of these changes is obscured by a number of factors, including heterogeneity and varying methodologies. The purpose of the current study was to obviate some of these problems. To do this, we used surface-based morphometry to derive distinct measures of cortical grey matter structure, including cortical thickness, surface area and cortical folding, and explored their relationship with BMI in a large sample of young to middle-aged adults with no reported clinical morbidities.

Materials and methods

Participants

T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from 203 subjects were analysed (age M=32.3, s.d.=7.7, range 18–50; 79 females). All subjects were scanned in the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre, as part of studies conducted by the Department of Psychiatry. Recruitment and MRI scanning of participants were approved by the National Health Service Local Research and University of Cambridge Psychology Research Committees. The scanning was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

All subjects were self-reported healthy, had no significant medical history, were not receiving any pharmacological treatment and reported no contraindications to MRI scanning. Ninteen subjects were smokers. BMI (weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres) was calculated for all participants from height and weight measures collected during the primary studies. The BMI range across the sample was 18.5–46.4 kg m−2 (M=28.5 kg m−2, s.d.=6.3 kg m−2).

MRI acquisition

T1 MRI scans were acquired on two 3-T scanners, the Siemens Trio and Siemens Verio (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). Magnetic resonance images were acquired with a sagittal MPRAGE T1-weighted, three-dimensional, inversion recovery gradient echo sequence with the following parameters: inversion time=900 ms; echo time=2.98 ms; repetition time=2300 ms; flip angle=9°; voxel dimensions=1 × 1 × 1 mm; and acquisition time=9.14 min.

MRI processing

Cortical reconstructions were generated using FreeSurfer,19 which was specifically developed for this purpose. The raw image data voxels were sub-sampled to voxels of size 1 mm3, following which the data were normalised for intensity. Radio-frequency bias field inhomogenieties were modelled and removed, followed by skull-stripping. The cerebral white matter was identified and the hemispheres were separated, tessellated and deformed to produce an accurate and smooth representation of the white–grey matter interface. Where inaccuracies occurred, reconstructions were edited manually. Surfaces were averaged across participants using a nonrigid high-dimensional spherical averaging method to align cortical folding patterns. This provides accurate matching of morphologically homologous cortical locations across subjects on the basis of each individual’s anatomy while minimising metric distortion. The target used for registration was the white–grey matter surface boundary. At each vertex, cerebral cortex thickness was quantified as the shortest distance between the white–grey matter surface and the grey matter–cerebrospinal fluid surface. Continuous maps of surface area of the white–grey matter boundary were obtained by computing the surface area of each vertex in the standardised, spherical atlas space, mapped to each subject’s native space. This provides a vertex-wise estimate of the relative surface area expansion or contraction of each location in atlas space. Cortical folding, or the degree of gyrification, was explored by computing the local gyrification index (LGI). In a vertex-wise manner, the LGI measures the ratio of cortex buried within sulcal folds and visible cortex on the outer surface. Cortical thickness and surface area maps were smoothed using a full width at half maximum 15-mm kernel, whereas LGI, due to its intrinsic smoothness, was smoothed with a smaller, full width at half maximum 5-mm kernel. For each subject, the global measures of total surface area, and average cortical thickness and LGI were also computed.

Statistical analyses

First, we analysed the association between BMI and global measures of average cortical thickness, total surface area and average LGI. This was examined using mixed effects modelling in R,20 with a random effect for individual subjects. A Bonferroni correction was adopted to account for the measurement of three variables, leading to a corrected threshold of P<0.017. Second, we examined the association between BMI and cortical thickness, surface area and LGI at each vertex of the cortex. This was performed using general linear modelling implemented in FreeSurfer. Correction for multiple comparisons was performed at the cluster level using Monte Carlo simulation (10 000 repetitions), PMC<0.05, in addition to a Bonferroni correction to account for the analysis of three measures over two hemispheres.

Age and gender were controlled for in all models, by including them as covariates in the models. Given that scanning was performed on two different 3-T scanners (using the same scanning sequence), in all statistical models, scanner type was included as a covariate. In addition, in the global and vertex-wise analyses of cortical thickness and LGI, and vertex-wise analysis of surface area, global surface area was used a covariate. As FreeSurfer produces separate outputs for each hemisphere for the above global measures, hemisphere was also included as a covariate into these models.

Results

One subject had an unusually thin cortex (<2mm). This subject was excluded as an outlier, which left 202 subjects for the analyses.

Analyses of global measures

There was no association between BMI and global measures of average cortical thickness, total surface area or average LGI (Table 1). Although the age and BMI of subjects were moderately correlated (r=0.31, P<0.0001), no multicolinearity was detected in the estimated models (the variance inflation factors of all the predictors in the models were <2).

Vertex-wise analyses

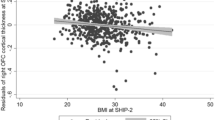

Although BMI was not associated with surface area or LGI on the vertex-wise level, it was negatively correlated with cortical thickness in two clusters. The first cluster was located in the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC; Talairach peak: 5, 26, −21; PMC=0.0001), expanding to the frontopolar and anterior cingulate. The second cluster was located in the left lateral occipital cortex (LOC; Talairach peak: −41, −86, −1; PMC=0.0001; Figure 1; Table 2). The percentage of variance of cortical thickness explained by BMI in the right vmPFC and left LOC was 12.25% and 12.96%, respectively. Scatter plots demonstrating the association of cortical thickness and BMI in these two clusters are shown in Figure 2. Post hoc contrasts revealed that lean (BMI<25) and overweight subjects (25⩽BMI<30) did not significantly differ in the thickness of the right vmPFC or left LOC (P=0.29 and P=0.34, respectively), while obese subjects (BMI⩾30) had significantly thinner cortices in these clusters, compared with both lean (P<0.0001 in both clusters) and overweight subjects (P<0.0001 in both clusters). Including smoking status as a covariate into the above models (global and vertex–wise) did not change the presented results.

Lateral and medial view of the two clusters (right vmPFC and left LOC) whose cortical thickness exhibited a negative correlation with BMI. The colour bar represents the logarithmic scale of Monte Carlo cluster-wise corrected P-values (−log(10)PMC). Red indicates positive and blue indicates negative association.

We explored whether there was overlap between the age-related and BMI-related effects on cortical thickness. The vertex-wise analysis of the association of cortical thickness with age, controlling for gender, scanner, global surface area and BMI revealed 11 distinct clusters in which age was negatively associated with cortical thickness (PMC<0.05, 10 000 repetitions: Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, including the interaction term in the model revealed that there was no region in the brain with an age-by-BMI interaction on cortical thickness (PMC<0.05, 10 000 repetitions), suggesting that the detected BMI-related thinning was separate from the age-related effects on thickness. Given the existing reports of gender differences in the association of obesity with brain structural changes (Supplementary Table 1), we also explored whether the established effect of BMI on cortical thickness could have been driven by the effects specific to men or women; however, there was no region in the brain with a gender-by-BMI interaction on cortical thickness (PMC<0.05, 10 000 repetitions).

Discussion

This study was carried out in the context of a growing, but highly inconsistent literature exploring the impact of adiposity on the brain’s grey matter structure. We optimised our approach by selecting a large set of structural images from adults who had no known clinical morbidity, and using a surface-based morphometric approach that permits the extraction of key parameters of cortical structure separately. We demonstrate in this large group of adults that there is no significant relationship between BMI, a well-established measure of adiposity, and global measures of cortical thickness, surface area or cortical folding. Using a spatially more precise, regionally specific approach, while there was no association between BMI and surface area or cortical folding, there was a robust reduction in cortical thickness associated with increasing BMI in two brain regions—the right vmPFC and left LOC. As age and global cortical surface area were controlled for, this is very unlikely to be an age-related or mechanical effect. Given that our volunteers reported no existing clinical condition increases our confidence that this specific alteration in cortical thickness is related to BMI, or BMI-associated subclinical metabolic dysregulations, rather than to clinical comorbidities of obesity.

There is growing evidence that cortical thickness has a systematic and interpretable relationship to underlying cytoarchitecture. Gradients in cortical thickness across the brain have been shown to reflect the brain’s functional hierarchies.18 Thinner cortex is thought to have higher neuronal density and shorter axonal/dendritic processes.21 The BMI-associated cortical thinning in the vmPFC and LOC therefore might be linked to greater neuronal density and reduced dendritic arborisation of these regions in obese individuals. Given that the thinning was observed over and above the effects of age and total surface area (in addition to age-related thinning, larger brains tend to have thinner cortices), we speculate that it reflects more fundamental changes in cytoarchitecture. Such changes have been linked to function: in the most extreme examples, changes in dendritic arborisation and spine structure are commonly observed in brain tissue of patients with various types of intellectual disabilities.22 Mutations affecting synaptic morphology and plasticity have been implicated in intellectual disability, schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders.23, 24 Furthermore, morphometric studies have linked variations in cortical thickness across normal populations to a number of cognitive attributes, including intelligence,25 executive function26 and attention.27 In short, cortical thickness s a parameter that relates to brain cytoarchitecture and function. A key question here is whether any conclusions can be drawn from the localisation of BMI-related changes observed in this sample and we begin by considering the known functions of these regions.

The vmPFC has a well-established role in decision-making, and particularly, in concert with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, in the control of goal-directed behaviour.28 Further, in a food-related task, De Wit29 demonstrated that the transition from goal-directed to habit-based responding is associated with an attenuation in responses in this region. We might therefore speculate that reduced thickness of the vmPFC is associated with a shift in balance between goal-directed and habitual or stimulus-dependent responding. Such a shift would account for an enhanced tendency to consume in response to the array of environmental cues that populate our environment and are continually driving us towards consumption, a drive that might otherwise be resisted by adherence to long-term goals and plans. It is noteworthy that, compared with lean subjects, poorer performance on the Iowa gambling task (originally developed and used by Bechara et al.30 in characterising decision-making deficits in vmPFC-lesioned patients) has been reported in obese subjects by multiple studies (reviewed in Vainik et al.31). Similarly, overeating and obesity have been linked to increased impulsivity—a personality trait operationalised through reduced response inhibition and/or steeper delay discounting.32 Studies of executive function, comprising various processes underpinned by goal-directed control, have also reported hypofunction in obese people and there are some experimental findings suggesting that poorer executive function predicts overeating and obesity.5, 31

Although we did not formally test for hemispheric specificity, the location of the vmPFC cluster on the right but not on the left is consistent with the observations of impaired decision-making in patients with right-sided vmPFC damage.33 Functional imaging studies have implicated the right prefrontal cortex in particular in the regulation of eating behaviour, and overeating has been associated with right frontal lesions (reviewed in Alonso-Alonso and Pascual-Leone34). Recent studies exploring the effects of transient transcranial direct current stimulation on eating behaviour have linked the activation of the right prefrontal cortex with decreased craving for foods and increased satiety.35, 36 Taken together, there is a convergence of several lines of research implicating the right prefrontal cortex in the control of eating behaviour, and perhaps therefore a prima facie case that the observations here and elsewhere11 of cortical thinning in this region are relevant to the behaviours involved in the persistence of elevated BMI. Interestingly, no adiposity-associated cortical thinning was observed in large sample of children (n=378), suggesting perhaps that prefrontal thinning, as a potential endophenotype of obesity linked to maladaptive food choices, only exerts its effect in adolescence or adulthood, when children begin making their own food choices.37 Altogether, although these reports provide a reasonable fit to our observations, we acknowledge that such a perspective is rather simplistic, based on the assumption of a one-to-one mapping between vmPFC thinning and an alteration in a particular cognitive process. Carefully designed prospective studies would need to be set-up to explore this possibility further.

In comparison with the vmPFC, the finding of cortical thinning in the lateral occipital cortex with increasing BMI was somewhat surprising. Interestingly, a recent study38 also found a negative correlation between BMI and thickness of the left LOC, approximately spanning the same region as detected in this study. However, the authors did not provide a specific interpretation of this finding. Equally, obese people have been shown to display a reduced functional connectivity of the left LOC during a picture-viewing task.39 This LOC region has been primarily associated with object recognition. It extends from the transverse occipital sulcus/intraparietal sulcus to the middle occipital gyrus and overlaps with regions that have been described as part of the dorsal attention functional network.40 This network is thought to direct attention to stimuli based on internal goals and to suppress responses to irrelevant stimuli, which has been described as goal-directed visual attention. Indeed, this same region has been reported to be consistently underactive in executive function tasks in adults and children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.41

There are also other strands of research that implicate the occipital cortex/visual attention in obesity. For example, obesity has been associated with reduced functional connectivity of the extrastriate cortex during visual processing of both food and non-food rewards.42, 43 Attention bias for food pictures in obesity has been described (reviewed in Nijs and Franken44), potentially representing a failure of shifting visual attention from salient food stimuli even after they have been devalued by satiation.45 Overall, although the BMI-related thinning of the LOC was not predicted, given that the finding was strong and indeed replicated in another study, we feel that it invites further exploration, particularly with regard to its potential functional implications.

So far, we have focused on the possibility that the structural alterations have a causal role in elevating BMI. But the converse possibility, that the observations are due to elevated BMI, is equally compelling. Indeed, the aforementioned study37 that failed to find an association between cortical thickness and overweight in children might also indicate that the BMI-associated thickness changes in the adult sample are secondary to adiposity.

Obesity is associated with several preclinical physiological dysfunctions that affect brain structure. Although our sample of volunteers did not have any clinical manifestations of disease, as we did not conduct laboratory tests of metabolic health, we cannot exclude the presence of subclinical metabolic dysfunctions, such as insulin resistance that could be related to the observed cortical thinning. Metabolically healthy obese individuals with undetected insulin resistance have been reported to have subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease such as increased carotid artery intima media thickness and coronary artery calcium that distinguish them from and confer a higher risk for cardiovascular disease than lean controls.46

For example, it is well established that obesity is associated with a state of low-grade systemic inflammation: hypertrophic adipocytes have been linked to the increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which in turn have been linked to the disruptions of insulin signalling and insulin resistance.2 In rodents, high-fat diets have been shown to induce an inflammatory response and subsequent damage in the hypothalamic region controlling food intake and energy expenditure.47, 48 Even though there is no evidence of pro-inflammatory state elsewhere in the brain, systemic markers of inflammation, such as increased levels of interleukin-6, have been linked to decreased global volume,3 and to reduced volumes of the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex.49 The fact that calorie restriction abolishes cytokine-driven reduction in brain volume strongly speaks in favour of obesity/inflammation as inducers of brain atrophy.50

Leptin has been proposed as another mediator of the effects of obesity on brain structure. Leptin-deficient rodents display several brain structural abnormalities, which can be improved with external leptin administration.51 In humans, increased leptin levels in middle age have been associated with a reduced risk of dementia in non-obese people.52 On the other hand, in groups of subjects with a wider range of BMIs, elevated levels of leptin have also been linked to brain volume deficits,53 perhaps due to leptin resistance.

Obesity has also been linked to increased cortisol secretion,54 which in turn has been linked to reduced brain volume.55 It is also often associated with increased incidence of hypoxic conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, asthma and several vascular pathologies leading to ischaemia,56 all of which have been associated with brain atrophy.57, 58

The regional specificity of the thickness effects observed might be viewed as speaking against the adiposity-related insult as the underlying cause of cortical thinning. However, there are certain observations that contest this, suggesting that particular brain regions are indeed more susceptible to atrophy linked to aging or external insults. For instance, it has been reported that the frontal lobe is more susceptible to age-related atrophy,59 and that the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex are more vulnerable to inflammatory damage.49 The regional specificity of the observed effects does not by itself rule out the possibility that these changes are consequential to obesity.

We acknowledge several limitations of the study. First, inherent to any cross-sectional design, such as ours, is the inability to determine the timeline of the development of observed differences, and whether the differences are causal or consequential, or if they predispose to obesity and are then worsened by increasing adiposity. Second, we did not have any specific measures of adiposity (such as absolute fat mass) and metabolic health. Third, we did not have any eating behaviour measures that could be related to the observed structural changes.

In summary, we sought to clarify the relationship between BMI and cortical grey matter structure in a large group of adults using structural MRI. Using a surface-based analysis, we were able to systematically examine distinct measures of cortical grey matter. Our findings of regional thinning demonstrate that, even in younger adults with no known clinical morbidities, adiposity is associated with changes in cortical morphology. The observation of vmPFC thinning in particular is highly consistent with the known functions of this region in value-based decision-making and mediating a balance between goal-directed and habitual responding.

References

WHO. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet N311 (Internet). WHO. 2015. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (cited on 26 February 2015).

Vachharajani V, Granger DN . Adipose tissue: a motor for the inflammation associated with obesity. IUBMB Life 2009; 61: 424–430.

Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Wolf PA, Seshadri S, Au R, Vasan RS et al. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with total brain volume: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology 2007; 68: 1032–1038.

Gustafson D, Rothenberg E, Blennow K, Steen B, Skoog I . An 18-year follow-up of overweight and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 1524–1528.

Smith E, Hay P, Campbell L, Trollor JN . A review of the association between obesity and cognitive function across the lifespan: implications for novel approaches to prevention and treatment. Obes Rev 2011; 12: 740–755.

Bobb JF, Schwartz BS, Davatzikos C, Caffo B . Cross-sectional and longitudinal association of body mass index and brain volume. Hum Brain Mapp 2014; 35: 75–88.

Gunstad J, Paul RH, Cohen RA, Tate DF, Spitznagel MB, Grieve S et al. Relationship between body mass index and brain volume in healthy adults. Int J Neurosci 2008; 118: 1582–1593.

Taki Y, Kinomura S, Sato K, Inoue K, Goto R, Okada K et al. Relationship between body mass index and gray matter volume in 1,428 healthy individuals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008; 16: 119–124.

Yokum S, Ng J, Stice E . Relation of regional gray and white matter volumes to current BMI and future increases in BMI: a prospective MRI study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 656–664.

Hassenstab JJ, Sweet LH, Del Parigi A, McCaffery JM, Haley AP, Demos KE et al. Cortical thickness of the cognitive control network in obesity and successful weight loss maintenance: a preliminary MRI study. Psychiatry Res 2012; 202: 77–79.

Marqués-Iturria I, Pueyo R, Garolera M, Segura B, Junqué C, García-García I et al. Frontal cortical thinning and subcortical volume reductions in early adulthood obesity. Psychiatry Res 2013; 214: 109–115.

Karlsson HK, Tuulari JJ, Hirvonen J, Lepomäki V, Parkkola R, Hiltunen J et al. Obesity is associated with white matter atrophy: a combined diffusion tensor imaging and voxel-based morphometric study. Obes Silver Spring Md 2013; 21: 2530–2537.

Kurth F, Levitt JG, Phillips OR, Luders E, Woods RP, Mazziotta JC et al. Relationships between gray matter, body mass index, and waist circumference in healthy adults. Hum Brain Mapp 2013; 34: 1737–1746.

Pannacciulli N, Del Parigi A, Chen K, Le DS, Reiman EM, Tataranni PA . Brain abnormalities in human obesity: a voxel-based morphometric study. Neuroimage 2006; 31: 1419–1425.

Horstmann A, Busse FP, Mathar D, Müller K, Lepsien J, Schlögl H et al. Obesity-related differences between women and men in brain structure and goal-directed behavior. Front Hum Neurosci 2011; 5: 58.

Moreno-López L, Soriano-Mas C, Delgado-Rico E, Rio-Valle JS, Verdejo-García A . Brain structural correlates of reward sensitivity and impulsivity in adolescents with normal and excess weight. PLoS One 2012; 7: e49185.

Panizzon MS, Fennema-Notestine C, Eyler LT, Jernigan TL, Prom-Wormley E, Neale M et al. Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb Cortex 2009; 19: 2728–2735.

Wagstyl K, Ronan L, Goodyer IM, Fletcher PC . Cortical thickness gradients in structural hierarchies. Neuroimage 2015; 111: 241–250.

Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI . Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage 1999; 9: 179–194.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team RC . nlme; Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models R package version 3:103 2012.

Cahalane DJ, Charvet CJ, Finlay BL . Systematic, balancing gradients in neuron density and number across the primate isocortex. Front Neuroanat 2012; 6: 20.

Huttenlocher PR . Dendritic and synaptic pathology in mental retardation. Pediatr Neurol 1991; 7: 79–85.

Gilman SR, Chang J, Xu B, Bawa TS, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M et al. Diverse types of genetic variation converge on functional gene networks involved in schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15: 1723–1728.

Van Bokhoven H . Genetic and epigenetic networks in intellectual disabilities. Annu Rev Genet 2011; 45: 81–104.

Narr KL, Woods RP, Thompson PM, Szeszko P, Robinson D, Dimtcheva T et al. Relationships between IQ and regional cortical gray matter thickness in healthy adults. Cereb Cortex 2007; 17: 2163–2171.

Burzynska AZ, Nagel IE, Preuschhof C, Gluth S, Bäckman L, Li S-C et al. Cortical thickness is linked to executive functioning in adulthood and aging. Hum Brain Mapp 2012; 33: 1607–1620.

Westlye LT, Grydeland H, Walhovd KB, Fjell AM . Associations between regional cortical thickness and attentional networks as measured by the attention network test. Cereb Cortex 2011; 21: 345–356.

Clithero JA, Rangel A . Informatic parcellation of the network involved in the computation of subjective value. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013; 9: 1289–1302.

De Wit S, Corlett PR, Aitken MR, Dickinson A, Fletcher PC . Differential engagement of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex by goal-directed and habitual behavior toward food pictures in humans. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 11330–11338.

Bechara A, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Anderson SW . Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition 1994; 50: 7–15.

Vainik U, Dagher A, Dubé L, Fellows LK . Neurobehavioural correlates of body mass index and eating behaviours in adults: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013; 37: 279–299.

French SA, Epstein LH, Jeffery RW, Blundell JE, Wardle J . Eating behavior dimensions. Associations with energy intake and body weight. A review. Appetite 2012; 59: 541–549.

Tranel D, Bechara A, Denburg NL . Asymmetric functional roles of right and left ventromedial prefrontal cortices in social conduct, decision-making, and emotional processing. Cortex 2002; 38: 589–612.

Alonso-Alonso M, Pascual-Leone A . The right brain hypothesis for obesity. JAMA 2007; 297: 1819–1822.

Fregni F, Orsati F, Pedrosa W, Fecteau S, Tome FAM, Nitsche MA et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation of the prefrontal cortex modulates the desire for specific foods. Appetite 2008; 51: 34–41.

Goldman RL, Borckardt JJ, Frohman HA, O’Neil PM, Madan A, Campbell LK et al. Prefrontal cortex transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) temporarily reduces food cravings and increases the self-reported ability to resist food in adults with frequent food craving. Appetite 2011; 56: 741–746.

Sharkey RJ, Karama S, Dagher A . Overweight is not associated with cortical thickness alterations in children. Front Neurosci 2015; 9: 24.

Veit R, Kullmann S, Heni M, Machann J, Häring H-U, Fritsche A et al. Reduced cortical thickness associated with visceral fat and BMI. Neuroimage Clin 2014; 6: 307–311.

García-García I, Jurado MÁ, Garolera M, Marqués-Iturria I, Horstmann A, Segura B et al. Functional network centrality in obesity: a resting-state and task fMRI study. Psychiatry Res 2015; 233: 331–338.

Corbetta M, Shulman GL . Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002; 3: 201–215.

Dickstein SG, Bannon K, Xavier Castellanos F, Milham MP . The neural correlates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: an ALE meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47: 1051–1062.

García-García I, Jurado MA, Garolera M, Segura B, Marqués-Iturria I, Pueyo R et al. Functional connectivity in obesity during reward processing. Neuroimage 2013; 66: 232–239.

Kullmann S, Pape A-A, Heni M, Ketterer C, Schick F, Häring H-U et al. Functional network connectivity underlying food processing: disturbed salience and visual processing in overweight and obese adults. Cereb Cortex 2013; 23: 1247–1256.

Nijs IMT, Franken IHA . Attentional processing of food cues in overweight and obese individuals. Curr Obes Rep 2012; 1: 106–113.

Castellanos EH, Charboneau E, Dietrich MS, Park S, Bradley BP, Mogg K et al. Obese adults have visual attention bias for food cue images: evidence for altered reward system function. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 1063–1073.

Roberson LL, Aneni EC, Maziak W, Agatston A, Feldman T, Rouseff M et al. Beyond BMI: The ‘Metabolically healthy obese’ phenotype & its association with clinical/subclinical cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality — a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 14.

Thaler JP, Yi C-X, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ, Hwang BH, Dietrich MO et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 153–162.

Velloso LA . The brain is the conductor: diet-induced inflammation overlapping physiological control of body mass and metabolism. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2009; 53: 151–158.

Marsland AL, Gianaros PJ, Abramowitch SM, Manuck SB, Hariri AR . Interleukin-6 covaries inversely with hippocampal grey matter volume in middle-aged adults. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64: 484–490.

Willette AA, Bendlin BB, McLaren DG, Canu E, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ et al. Age-related changes in neural volume and microstructure associated with interleukin-6 are ameliorated by a calorie-restricted diet in old rhesus monkeys. Neuroimage 2010; 51: 987–994.

Hashimoto R, Matsumoto A, Udagawa J, Hioki K, Otani H . Effect of leptin administration on myelination in ob/ob mouse cerebrum after birth. Neuroreport 2013; 24: 22–29.

Lieb W, Beiser AS, Vasan RS, Tan ZS, Au R, Harris TB et al. Association of plasma leptin levels with incident Alzheimer’s disease and MRI measures of brain aging: The Framingham Study. JAMA 2009; 302: 2565–2572.

Pannacciulli N, Le DSNT, Chen K, Reiman EM, Krakoff J . Relationships between plasma leptin concentrations and human brain structure: a voxel-based morphometric study. Neurosci Lett 2007; 412: 248–253.

Björntorp P . Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities? Obes Rev 2001; 2: 73–86.

Simmons NE, Do HM, Lipper MH, Laws ER Jr . Cerebral atrophy in Cushing’s disease. Surg Neurol 2000; 53: 72–76.

Zammit C, Liddicoat H, Moonsie I, Makker H . Obesity and respiratory diseases. Int J Gen Med 2010; 3: 335–343.

Gale SD, Hopkins RO . Effects of hypoxia on the brain: neuroimaging and neuropsychological findings following carbon monoxide poisoning and obstructive sleep apnea. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004; 10: 60–71.

Yoshimitsu T, Hirakata H, Fujii K, Kanai H, Hirakata E, Higashi H et al. Cerebral ischemia as a causative mechanism for rapid progression of brain atrophy in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 2000; 53: 445–451.

Raz N . Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance: integration of structural and functional findings. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA (eds), The Handbook of Aging and Cognition 2nd ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000. pp 1–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants and the staff of the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre. This work was supported by the Bernard Wolfe Health Neuroscience Fund (NM, HZ, ISF and PCF), the Wellcome Trust (RGAG/144 to NM, RGAG/188 to ISF and RNAG/259 to PCF) and the Medical Research Council (G0701497 to KDE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ETB is employed half-time by the University of Cambridge and half-time by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); he holds stock in GSK. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Medic, N., Ziauddeen, H., Ersche, K. et al. Increased body mass index is associated with specific regional alterations in brain structure. Int J Obes 40, 1177–1182 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.42

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.42

This article is cited by

-

Body composition is related to cognitive function among young adults in Ghana

BMC Psychology (2024)

-

Brain functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging of obesity and weight loss interventions

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Insulin Resistance-Varying Associations of Adiposity Indices with Cerebral Perfusion in Older Adults: A Population-Based Study

The Journal of nutrition, health and aging (2023)

-

Relationship between impulsivity, uncontrolled eating and body mass index: a hierarchical model

International Journal of Obesity (2022)

-

Obesity and brain structure in schizophrenia – ENIGMA study in 3021 individuals

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)