Abstract

Many human diseases, including metabolic, immune and central nervous system disorders, as well as cancer, are the consequence of an alteration in lipid metabolic enzymes and their pathways. This illustrates the fundamental role played by lipids in maintaining membrane homeostasis and normal function in healthy cells. We reviewed the major lipid dysfunctions occurring during tumor development, as determined using systems biology approaches. In it, we provide detailed insight into the essential roles exerted by specific lipids in mediating intracellular oncogenic signaling, endoplasmic reticulum stress and bidirectional crosstalk between cells of the tumor microenvironment and cancer cells. Finally, we summarize the advances in ongoing research aimed at exploiting the dependency of cancer cells on lipids to abolish tumor progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

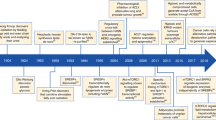

Metabolic reprogramming is now firmly established as a hallmark of cancer.1 Tumors share a common phenotype of uncontrolled cell proliferation and for this they must efficiently generate energy and biomass components in order to expand and disseminate. The required changes in metabolic phenotype are directly driven by successive oncogenic events (oncogene activation and loss of tumor suppressors), and by the constraints imposed by the tumor microenvironment (TME) (poor oxygenation and nutrient scarcity).2, 3 Hence, cancer cells show an expanded metabolic repertoire that affords the flexibility to withstand and grow in this harsh tumor environment. The first adaptive events in tumor metabolism to be identified are an exacerbated glucose uptake and glycolysis utilization leading to increased lactate production (that is, the Warburg effect4).5, 6 Cancer cells also rely on glutamine consumption, which provides carbon and amino-nitrogen needed for amino-acid, nucleotide and lipid biosynthesis.6, 7 Functionally dependent on glucose and glutamine catabolic pathways but commonly disregarded in the past, alterations in lipid- and cholesterol-associated pathways encountered in tumors are now well recognized and more frequently described (Figure 1).8, 9, 10 Highly proliferative cancer cells show a strong lipid and cholesterol avidity, which they satisfy by either increasing the uptake of exogenous (or dietary) lipids and lipoproteins or overactivating their endogenous synthesis (that is, lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis, respectively) (Figure 1). Excessive lipids and cholesterol in cancer cells are stored in lipid droplets (LDs), and high LDs and stored-cholesteryl ester content in tumors11, 12, 13, 14 are now considered as hallmarks of cancer aggressiveness.13, 15, 16, 17 Colon cancer stem cells showed higher LD amount than their differentiated counterparts, as revealed by Raman spectroscopy imaging.18 Moreover, LD-rich cancer cells are more resistant to chemotherapy.11 Therefore, using Raman-based imaging to define tumor LD content is an emerging tool for monitoring or predicting drug treatment response in cancer patients.19, 20 Moreover, LD content, especially cholesteryl ester, is mobilized by pancreatic cancer cells under a restricted cholesterol-rich low-density lipoprotein (LDL) supply14 and limiting LDL uptake reduces the oncogenic properties of pancreatic cancer cells and rendered them more sensitive to cytotoxic drugs.14 Survival and metastatic spreading of cancer cells also rely on exogenous fatty acid (FA) uptake and consumption, the latter through fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) pathway, even in cells exhibiting high lipogenic activities (Figure 1).21, 22, 23 FAO is considered as the dominant bioenergetic pathway in non-glycolytic tumors, such as prostate adenocarcinoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.24, 25, 26 The dependence of cancer cells on FAO is further heightened in nutrient- and oxygen-depleted environmental conditions.22 Then, therapeutic strategies designed to exploit the lipid-related metabolic dependence in cancer must be carefully targeted to achieve the desired effect and avoid harmful consequences for normal metabolic functions.

A simplified map of the main altered lipid metabolic pathways in cancer cells. Lipid metabolic network (blue) includes import/export and catabolic pathways (FAO) as well as de novo synthesis pathways, such as lipogenesis (that is, synthesis of TGs and PLs) and cholesterol synthesis. Glucose- and/or glutamine-derived citrate, provided by the increased glycolysis and/or glutaminolysis (orange), are common precursors of lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis. Cancer cells can also take up exogenous cholesterol, transported by LDL and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), to meet their cholesterol requirement. When cholesterol, PLs and TGs are in excess in tumors, they are exported into circulation as high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) or locally stored into LDs. Exogenous FAs taken up by cancer cells are broken down to produce energy through mitochondrial FAO process. TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle αKG, α-Ketoglutarate.

Lipids encompass a vast class of biomolecules of unique chemical structure in terms of FA chain length, number and location of double bonds as well as backbone structures (glycerol and sphingoid bases). The functional consequence of this lipid diversity is still not fully understood. However, lipids have been described to exert multiple biochemical functions during cancer development. Historically, they were viewed as passive components of cell membranes where they form lipid rafts that facilitate signaling protein recruitment and thus protein–protein interactions promoting signal transduction. Important changes in lipid composition (saturated (SFA) vs unsaturated FA) and abundance severely alter membrane fluidity and protein dynamics. For example, an increase in saturated phospholipids (PLs) markedly alters signal transduction, protects cancer cells from oxidative damage such as lipid peroxidation and potentially inhibits the uptake of chemotherapeutic drugs.27, 28 In addition to their structural roles, lipids orchestrate signal transduction cascades and can also be broken down into bioactive lipid mediators, which regulate a variety of carcinogenic processes, including cell growth, cell migration and metastasis formation.29, 30, 31

In this review, we summarize the major lipid dysfunctions identified in various tumors using gene candidate or ‘-omics’ approaches. We focus on the impact of lipid content alterations on intracellular oncogenic signaling and on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis. We also detail the lipid exchange between stroma cellular components and cancer cells. Finally, we present advances in the therapeutic targeting of metabolic actors associated with lipid pathways in preclinical and clinical development.

Lipid reprogramming in tumors

Lipid alterations identified from tumor-specific gene expression profiling

Candidate-gene expression studies identified upregulated transcripts involved in lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis pathways (Figure 1), which are essential for development and progression of a wide variety of tumors. Increased expression of lipogenic enzymes, such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FASN), and ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) that promote also cholesterol synthesis, represent a nearly-universal phenotypic alteration in most tumors.32, 33 FASN overexpression predicts poor prognosis in cancer patients.34 Its expression levels appear at the precancerous lesion stage and persist in metastatic breast and prostate tumors.34 As these initial observations, many other candidate genes, involved in cholesterol-related pathways (uptake, synthesis and storage) and FAO, proved to be crucial in supporting malignancy.8, 10, 35 FAO-limiting enzymes, the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 isoforms A and C (CPT1A and C) are overexpressed in many human tumors.36, 37, 38 CPT1C upregulation, induced by AMPK and p53, has been shown to protect cancer cells from death when they are under deprived glucose and oxygen conditions.36, 38, 39 Inversely, knockdown of CPT1 sensitizes cancer cells to radiotherapy and apoptosis inducers.40, 41, 42

Our large-scale microarray profiling, centered on metabolic genes, reveals lipid pathways as the most altered metabolic routes in pancreatic tumors, especially activated cholesterol and LDL metabolisms.14 These tumors harbor also specific alterations in metabolic pathways related to lipid messengers (phosphatidylinositols, PIs), lipid mediators (leukotrienes) and structural lipids (glycosphingolipids).14 This lipid signature unravels the high dependence of pancreatic tumors on cholesterol and identifies exogenous cholesterol uptake, through LDLR, as the major cholesterol pathway mediating tumor growth. Colorectal cancer (CRC) lipid signature, defined from a limited lipid-related genes expression profiling, reveals four genes (ABCA1, ACSL1, AGPAT1 and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD)) overexpressed only in stage II CRC patients with a high risk of relapse. This signature displays stronger power and accuracy than the currently used clinical classification.43

Lipid alterations identified from tumor-specific lipid profiling

Recent advances in lipid analytical and imaging technologies, including electrospray ionization, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) and Raman scattering microscopy, have greatly progressed such lipidomic analysis.44 Raman-based imaging offers lipid compositional mapping of cellular compartments, such as LDs.26, 45 These complementary approaches provide crucial information on tumor lipid phenotype, in particular abundance, FA composition and spatial distribution of lipid classes within tumors. Over the past few years, much effort has surrounded establishing PL signature of malignant tumors. This signature segregates malignant tumors from their benign counterparts as well as localized tumors from advanced ones. Indeed, breast tumors, when compared with adjacent normal tissue, have been characterized by a striking increase in membrane phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine and in PL-induced cell signaling, PI.46, 47 In addition to these changes in PL amounts, the phosphatidylcholine content was found to be enriched in SFA, and this phosphatidylcholine composition was correlated with high tumor grade and poorer overall survival.46 This membrane lipid saturation, a feature shared by all lipogenic tumors,27 reduced membrane fluidity and dynamics48 and increased chemotherapy resistance.27 The specific PI signature revealed a shift toward polyunsaturated FA chain composition in PI from invasive breast cancers when compared with that in PI from in situ carcinoma.49 These findings highlight significant differences in FA composition depending on PL class and tumor grade. Unlike breast tumors, the lipid signature of Myc-induced lymphoma is characterized by reduced phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine and PI amounts and by elevated monounsaturated FA-phosphatidylglycerol (PG) levels when compared with normal tissues.50 The increased PG is also found in renal cell and hepatocellular carcinomas.51, 52 PG serves as a precursor of cardiolipin, which is found almost exclusively in mitochondrial membranes and intimately involved in maintaining mitochondrial functionality and membrane integrity. An abnormal cardiolipin molecular species distribution and a decrease in CL content in brain tumor mitochondria, revealed by shotgun lipidomic analysis, lead to irreversible respiratory injury and may impede the use of alternative energy sources to glucose.53

Lipidomic profiling has revealed unsuspected and recurrent lipid changes at the class and molecular species levels in cancer cells. As previously discussed, PL-specific composition may help to discriminate low- and high-grade tumors as well as malignant cells from benign ones.46, 47, 49, 50 Moreover, combined with transcriptome/proteome analyses, lipidomic data could also unravel new potential lipid-related targets for drug development or new treatments combining inhibitors of these targets with currently used chemotherapy.

Lipid rafts in cancer cell signaling

Increased lipid rafts in tumors

Cell membranes contain different classes of lipids, some of which, in particular cholesterol and sphingolipids, form specific planar microdomains known as lipid rafts (Figure 2).54 These differ from the cavin and caveolin protein-enriched invaginated-lipid rafts known as caveolae.28 Both are essential not only for membrane protein dynamics and trafficking but also for cell survival and cell death program execution.55 In cancer cells, a wide range of signaling proteins and receptors regulating pro-oncogenic and apoptotic pathways during the early, advanced and metastatic stages of carcinogenesis reside in lipid rafts (Figure 2).55 Moreover, lipid rafts/caveolae and their main component, cholesterol, are enhanced in membrane of multiple cancer cells56, 57, 58, 59, 60 as well as in membranes of tumor-released exosomes.61

Lipid rafts as platforms for cell signaling. (a) Lipid rafts are formed by a phospholipid bilayer enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids and resident signaling proteins (AKT) and receptors (GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase including growth factor receptor (GFR); CXCR4, C-X chemokine receptor 4). Once activated by their respective ligands, the receptors recruit different signaling effectors that promote cell survival, cell migration and cell invasion, all of which contribute toward tumor growth. (b) Aggregation of death receptors (DR4/DR5, Fas) in lipid rafts forms CASMERs. Recruitment of CASMERs in a restricted space enhances fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD)/Caspase-8 death signaling pathway when compared with apoptotic signal induced by the activation of non-clustered death receptors.

Impact of disrupted lipid raft integrity on tumor cell fate

Decreasing cholesterol content with membrane-depleting agents (methyl-β-cyclodextrin) or cholesterol synthesis inhibitors (statins) helped to decrypt the oncogenic signaling pathways whose activation is entirely dependent on lipid raft integrity. Anchored-lipid raft AKT protein has been extensively investigated in cancer cells (Figure 2a).62, 63 Its aberrant activation, contributing to tumor development and invasiveness,64, 65 correlates with increased lipid rafts in cancer cells.66, 67 Lipid raft disruption inhibits AKT activation63, 67, 68 and then reduces tumor cell proliferation (Figure 2a).66 Lipid rafts also exert crucial roles in cancer dissemination. By regulating cytoskeletal reorganization and focal adhesion dynamics, lipid rafts regulate cancer cell migration.69, 70 They are also important for ligand-directed migration of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma cells by maintaining C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) dimer conformation.71

Novel raft-based entities, known as clusters of apoptotic signaling molecule-enriched rafts (CASMERs), have been recently described (Figure 2b).55 These are constituted by co-aggregation of lipid rafts with death receptors (Fas/CD95, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand or TRAIL) and their downstream apoptotic molecules. This configuration activated efficiently the apoptotic response independently of death receptor ligands (FasL and TNFα) (Figure 2b). CASMER formation and its subsequent Fas/CD95 or TRAIL-induced cell death can be inhibited by cholesterol-depleting agents, as described in leukemia cells and non-small cell lung carcinoma.55, 72 Similarly, resveratrol induced-CASMER formation and sensitization of colon carcinoma cells to death receptor-mediated apoptosis are prevented by cholesterol membrane depletion.73

These findings provide evidence for multiple oncogenic events depending on lipid raft integrity. Disruption of these microdomains, which act as hubs linking receptors to their signaling effectors, thus represents a valid therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment.

Complex lipid and cholesterol alterations inducing ER stress

Cancer cell fate following persistent ER stress

The ER ensures protein folding and maturation as well as calcium homeostasis and regulates lipid metabolic processes. Accumulation of misfolded proteins, membrane lipid saturation or imbalanced calcium homeostasis leads to ER stress (ERS) and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR).74 UPR is transduced through three distinct ERS sensor proteins: ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6), PERK (protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase) and IRE1 (inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endonuclease 1), which either reduce protein translation or increase ER-associated protein degradation to maintain cell survival. UPR can evoke cell-cycle arrest in G1 phase leading to the accumulation of quiescent cancer cells awaiting a more permissive environment to re-enter the cell cycle.75 When cancer cells are submitted to persistent stresses (that is, hypoxia, membrane lipid saturation and nutrient deprivation), UPR leads to cell death.

Changes in complex lipid/cholesterol content and composition cause ERS-induced apoptosis

Membrane PL saturation disturbs ER structure66 and then impairs ER homeostasis,76, 77 a phenomenon commonly encountered in various cancer cells.27 Lipid saturation, induced by the loss of the enzyme SCD1, was shown to promote ERS-activated apoptosis.78 A similar cancer cell fate is noticed following inactivation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein, the major transcriptional regulator of lipogenic genes, in a lipid-poor environment.79 This lipotoxic effect is abrogated by addition of exogenous unsaturated lipids80 or by re-expressing SCD1.79 Recently, imbalanced cholesterol homeostasis, leading to free cholesterol (FC) overload, was shown to induce ERS in cancer cells. Indeed, FC accumulation in HepG2 cells, induced by antitumor alkylphospholipids (perifosine, miltefosine and edelfosine),81 triggers an increase in the ERS marker, CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein).82 Similarly, inhibitors of cholesterol esterification, targeting the enzyme sterol-O-acyl transferase 1 (SOAT1), activated ERS markers in adrenocortical adenocarcinoma cells.83 High ceramide levels in ER, resulting from an increase either in membrane sphingomyelin hydrolysis or in ceramide de novo synthesis, can also induce ERS.84, 85 Cannabinoids, by increasing synthesized ceramide content, trigger ERS-induced cell death in human glioma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.86, 87, 88 This process results from a p8-dependent upregulation of CHOP/ATF4 branch of UPR.87 Finally, increased exogenous ceramide uptake leads to apoptosis in various human cancer cells, including head and neck squamous carcinoma cells89, 90 and salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma cells.91

Data demonstrating ERS-induced apoptosis in cancer cells submitted to complex lipid and/or cholesterol homeostasis alterations open a promising therapeutic window. It allows us to predict that manipulating cholesterol and lipid supplies or metabolic pathways leading to PL saturation, FC or ceramide accumulation may impede tumor growth and dissemination.

Tumor-stroma communication mediated by lipids

In human cancers, the TME, formed by extracellular matrix components and numerous stromal cells including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), infiltrating immune cells, adipocytes, nerve cells, vascular/lymphatic endothelial cells, represents up to 90% of the tumor mass.92 A molecular dialog between cancer cells and adjacent CAFs or immune cells has been clearly demonstrated to support tumor growth and progression. Today, the central role played by bioactive lipids and FAs as mediators of this crosstalk between cancer cells and stroma is increasingly recognized.

Cancer-stroma interplay through free FAs

Numerous tumors grow in the vicinity of adipocytes or metastasize to adipocyte-rich host environment. Metastatic ovarian cancer cells home to omental adipose tissue, which constitutes an important reservoir of triglycerides (TGs).93 Hydrolysis of these TG provides free FA (FFA), which are taken up and used as energy source by metastatic ovarian cancer cells (Figure 3).93 A similar FA exchanges also exist between adipocytes and metastatic bone marrow-derived prostate cancer cells.94 This adipocyte-cancer cell dialog is an adaptive metabolic process set up by cancer cells to take full advantage of the lipids stored in TME cells. FA translocation from stromal cells to cancer cells can be mediated by lipoproteins, serum albumin and exosomes. It is tempting to speculate that FA carried by serum albumin could be taken up by cancer cells through macropinocytosis: a non-receptor mediated endocytosis process constituting part of an ancestral strategy used to salvage extracellular nutrients.95, 96 Exosomes can also serve as carriers of FA and are taken up by recipient cells (Figure 3). Their content, similar to that of parental cells, is mostly enriched in SFA more than monounsaturated FA and polyunsaturated FA, the latter group of which is most represented by arachidonic acid, the precursor of eicosanoids (prostaglandins and leukotrienes).97 Once internalized, exosomes transfer their lipid material to the receiving cell.98 The ensuing lipid accumulation alters lipid homeostasis thereby triggering ERS-induced apoptosis and/or disturbing lipid raft signaling, as discussed in the previous section. Beloribi et al.99 also demonstrated that synthetic exosome-like nanoparticles, mimicking the lipid composition of cancer exosomes, inhibit the Notch survival pathway leading to differentiated pancreatic cancer cell death (Figure 3).

Tumor–stroma bidirectional dialog. Schematic representation of lipid exchanges between cancer cells and the different cell types found in the TME. In adipocytes adjacent to cancer cells, the hydrolysis of TG, stored in LDs, releases free fatty acids (FFAs) which are taken up by cancer cells, transported through fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) and degraded to provide ATP needed for their growth. Bioactive lipids secreted by cancer cells, PGE2 and S1P, exert their effects on stromal cells through paracrine mechanisms. The PGE2, transported or not by exosomes, promotes angiogenesis and also immunosuppression. The latter effect results from an activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and differentiation of monocytes into suppressor macrophages. Moreover, tumor-derived PGE2 induces kynurenine secretion by CAFs which in turn promote cancer cell invasiveness. S1P, by its binding on its specific receptor, promotes cancer cell proliferation and angiogenesis/lymphangiogenesis in an autocrine and paracrine manner, respectively. Taken together, FFA and free bioactive lipids contribute toward promoting tumor growth. Exosomes in TME contain high lipid levels within the membrane and lumen, and therefore constitute extracellular lipid sources which can be internalized by cancer cells and are responsible for the increased cell lipid concentration which triggers an ERS-induced cell death.

Tumor–stroma dialog orchestrated by prostaglandins

An increase in prostaglandins (PGs) in cancer cells not only promotes tumor growth in a paracrine manner, but also coordinates the complex dialog between tumor cells and the surrounding stromal cells. This crosstalk evades the immune system attack by promoting immunosuppression (Figure 3).30 Breast tumor-derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been shown to induce, through an exosome-dependent transport, myeloid-derived suppressor cell activation, which in turn promotes tumor growth.100, 101 Moreover, PGE2 was found to promote the differentiation of monocytes into tumor-associated suppressive macrophages in cervical tumors.102 A pro-angiogenic activity of tumor-derived PGE2 has also been demonstrated in different cancers.30, 103, 104, 105 PGs released from cancer cells expressing the rate-limiting enzyme of PG synthesis, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), trigger endothelial cell migration in vitro and neovascularization in vivo.103, 104 Recently, a PGE2-dependent dialog between breast tumor cells and CAFs has been demonstrated. Tumor-derived PGE2 activates the CAF-dependent secretion of a tryptophan catabolite, the kynurenine, which in turn increases cancer cell invasiveness (Figure 3).106

Sphingolipid derivative as a mediator of tumor–stromal cell communication

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), another bioactive lipid secreted by cancer cells, induces angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis through its binding on S1P receptor 1, and facilitates tumor growth and metastasis formation.107, 108 Moreover, high extracellular S1P levels, induced by overexpression of the upstream regulatory sphingosine kinase, increases migration and tube formation in co-cultured vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells (Figure 3).109

Together, these findings highlight the crucial role of lipids and their modes of transport in supporting the tumor-TME dialog, which is essential for tumor cell proliferation and dissemination.

Lipids as cancer therapy targets

Targeting the lipid and cholesterol dependence of cancer cells

Inhibitor agents directed against lipogenic enzymes (FASN, ACLY and ACC) have been the subject of numerous studies; and their efficacy as anticancer therapies have been proven in various preclinical models of carcinogenesis (Table 1).110, 111, 112 However, high adverse side effects of FASN-targeting drugs have precluded their clinical development. Numerous studies, using pharmacological agents targeting liver X receptor (LXR), a crucial transcriptional regulator of cholesterol homeostasis, have shown relevant anticancer roles but also with undesired side effects.113 Recently, an LXR inverse agonist (SR9243), devoid of toxic side effects and with similar impacts on colon cancer, holds significant promise for cancer therapy (Table 1).114 Alternative therapies directed against SCD1 enzyme have shown a delay in tumor growth in various mouse xenograft models.115 Interestingly, the high dependency of cancer cells on SFA can be exploited to increase tumor-drug delivery, as loading drugs in liposomes enriched in saturated phosphatidylcholine has been shown to reduce the metastatic spread of pancreatic cancer in vivo.116 The use of CPT1 inhibitors (that is, etomoxir or ranolazine) provides beneficial effects in FAO-dependent tumors, notably in prostate cancer42 and in human leukemia when they are combined with pro-apoptotic agents.40 Recently, a novel CPT1a inhibitor, ST1326, has been shown to drive leukemia cells toward apoptosis. This apoptotic effect results from an accumulation of palmitate.37 Several strategies have been developed to target cholesterol or cholesterol/isoprenoid synthesis. Oxidosqualene cyclase inhibitor (Ro 48-8071)117 or statins reduced tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis incidence in mouse carcinogenesis models (Table 1).118 However, despite promising preclinical results, the use of statins as monotherapy failed to improve patient outcome in many cancers119 because in addition to inhibiting cholesterol synthesis, statins increase circulating cholesterol supply through LDLR. In contrast, cholesterol depletion in high LDLR-expressing cancer cells by combining chemotherapy with the blockade of LDLR represents a promising alternative therapeutic option to limit pancreatic tumor growth. Indeed, LDLR silencing potentiates tumor regression induced by chemotherapy.14 Finally, pharmacological inhibitors of SOAT1 enzyme (avasimibe, Sandoz 58-035) (Table 1), through limiting cholesteryl ester storage, have been shown to suppress tumor growth in prostate cancer xenograft models.13

Lipid raft targeting

As discussed above, anticancer drugs that disturb membrane cholesterol content can be used to impair lipid raft-dependent cell survival or cell death pathways. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin depletes membrane cholesterol and inhibits human melanoma, breast and ovarian cancer growth without elicited acute systemic cytotoxicity (Table 1).68, 120 Moreover, when combined with tamoxifen, methyl-β-cyclodextrin slows down melanoma cancer progression by inhibiting AKT and favoring drug uptake,121 probably through increased membrane permeability. By increasing cholesterol ABCG1-dependent efflux, LXR agonist abrogates the lipid raft-dependent AKT survival pathway and then induces prostate cancer cell apoptosis (Table 1).122 In glioblastoma, such LXR agonist induces tumor cell death in vivo; an effect resulting from an increase in both LDLR degradation and ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux.123 Other pharmacological treatments known to reduce lipid raft-associated cholesterol, such as inhibitors of cholesterol synthesis, have been shown to promote prostate cancer growth arrest and cell death.67, 124 Finally, different therapeutic drugs, promoting CASMER formation, are being investigated. By their accumulation in cell membrane, synthetic alkylphospholipids (edelfosine, perifosine)125, 126 and plant-derived compounds (Avicin D, resveratrol)127, 128 promote the recruitment of death receptors, including Fas and TRAIL, into lipid rafts (Table 1). This results in the activation of ligand-independent Fas and/or TRAIL apoptotic pathways in various cancer cells (Figure 2).

Therapies promoting ERS-induced apoptosis

The disruption of lipid homeostasis induces ERS and then cancer cell death when the ERS exceeds the cell’s adaptive mechanisms. Nelfinavir and its analogs inhibit Site-1 and Site-2 proteases (S1P and S2P), both of which are required for the release of the mature and transcriptionally-active form of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1. The ensuing decrease in lipogenic gene expression induces ERS and apoptosis in liposarcoma129 and castration-resistant prostate cancer cells.130 This compound associated with chemotherapy is currently in phase II clinical trials for myeloma, glioblastoma, pancreatic and lung cancer (Table 1).131 Other chemical compounds, Orlistat and C75, by abrogating the activity of the rate-limiting enzyme of lipogenesis FASN, trigger activation of the UPR and cell death in prostate cancer cells (Table 1).132 Recently, mitotane has been demonstrated to have an anticancer role, impeding cholesterol esterification by inhibiting SOAT1 enzyme and consequently inducing an overload of cytotoxic FC within adrenocortical carcinoma cancer cells.83 This alteration in lipid homeostasis causes ERS-induced apoptosis and seems to be specific to steroidogenic cancer cells. A similar effect, with lower efficacy, is observed with the Sandoz 58-035 SOAT inhibitor (Table 1).83 As prostate tumors also exhibit high SOAT1 expression levels, it is possible that mitotane may promote ERS-induced apoptosis. Preclinical investigations are ongoing on the use of an inhibitor of SCD1 (A939572) which triggers SFA accumulation, in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Its combined administration with tyrosine kinase or mTOR inhibitors appears to improve its efficiency and reduce its cytotoxicity.133 Impaired HIF2α/PLIN2-dependent lipid storage in clear cell renal cell carcinoma disturbs ER homeostasis and enhances sensitivity to ERS-inducing agents.11 Hence, coupling proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib known to induce the UPR,134 with HIF2α-specific inhibitors currently under development for treating clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients, could be a rational therapeutic approach. Finally, treatments leading to ceramide accumulation and then ERS-induced apoptosis have shown encouraging results in many preclinical cancer models (Table 1).135, 136 Indeed, cannabinoid receptor agonists, supporting ceramide-dependent pro-apoptotic cascade, in combination with conventional chemotherapy could be therapeutically exploited for the management of glioblastoma.136

Disrupting the lipid-mediated dialog between cancer cells and TME cells

Targeting either the lipid messengers or their carriers between stromal and tumor cells constitutes an interesting anticancer therapeutic route to continue investigating. The use of COX-2 enzyme inhibitor, Celecoxib, to disrupt PG synthesis has revealed its strong antitumoral and antimetastatic effect in various preclinical models.137, 138 Moreover, it can attenuate patient chemoresistance as well as undesired side effects of anticancer drugs in various cancers.137, 139, 140, 141, 142 One clinical study on breast cancer patients is ongoing to evaluate the effect of Celebrex (that is, celecoxib) alone or in combination with vitamin D (Clinical Trial No NCT01769625). New COX-2 inhibitors with lower adverse side effects, such as CG100649,143 and antagonists of PGE2 receptors30 have shown promising results in multiple cancer preclinical models. Regarding the bioactive lipid S1P, its neutralizing monoclonal antibody, sphingomab, has proven to be effective at inhibiting angiogenesis, tumor growth and metastasis in multiple cancer cell lines.107 Similar effects on cancer progression have been observed with inhibitors of its upstream regulatory sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1)144 or its receptor (S1P receptor 1).145 Moreover, sphingomab increases the sensitivity of RCC-bearing mice to sunitinib treatment, which inhibits VEGFR2 tyrosine kinase.146 Hence, sphingomab constitutes a promising therapy for RCC non-responder patients. In the extracellular space, all these bioactive lipids can be found within exosomes, hence alternative strategies aiming at decreasing exosome generation and secretion or modifying the exosome content within tumors, should be considered in the future as potential cancer treatments.

Conclusion

Compelling evidence gained from untargeted/targeted lipidomics studies, cancer preclinical models and clinical trials, has revealed the crucial role of lipid classes and molecular species in supporting tumor growth and metastatic dissemination. Disrupting lipid metabolic pathways to unbalance lipid homeostasis, through the targeting of enzymes, receptors or bioactive lipids, induces tumor regression and inhibits metastatic spread. These effects result from: (1) fundamental changes in lipid raft composition; or (2) sustained ERS-induced UPR, both leading to cancer cell death; or (3) disruption of the lipid-mediated crosstalk between stromal and tumor cells, impeding the pro-tumoral function of stromal cells. Continued efforts to identify all the key actors within these different processes may offer novel metabolic targets for cancer treatment. These clinical strategies, based on the tumor dependence towards lipids, may hold promise for cure the most intractable cancers, including pancreatic and lung cancers, which will become the two deadliest cancers in horizon 2030.

References

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA . Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144: 646–674.

Boroughs LK, DeBerardinis RJ . Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17: 351–359.

Qiu B, Simon MC . Oncogenes strike a balance between cellular growth and homeostasis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015; 43: 3–10.

Warburg O . On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956; 123: 309–314.

Ying H, Kimmelman AC, Lyssiotis CA, Hua S, Chu GC, Fletcher-Sananikone E et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell 2012; 149: 656–670.

Gaglio D, Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Hiller K, Danna LS, Balestrieri C et al. Oncogenic K-Ras decouples glucose and glutamine metabolism to support cancer cell growth. Mol Syst Biol 2011; 7: 523.

Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature 2013; 496: 101–105.

Baenke F, Peck B, Miess H, Schulze A . Hooked on fat: the role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. Dis Model Mech 2013; 6: 1353–1363.

Ackerman D, Simon MC . Hypoxia, lipids, and cancer: surviving the harsh tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol 2014; 24: 472–478.

Cruz PM, Mo H, McConathy WJ, Sabnis N, Lacko AG . The role of cholesterol metabolism and cholesterol transport in carcinogenesis: a review of scientific findings, relevant to future cancer therapeutics. Front Pharmacol 2013; 4: 119.

Qiu B, Ackerman D, Sanchez DJ, Li B, Ochocki JD, Grazioli et al. HIF2alpha-dependent lipid storage promotes endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2015; 5: 652–667.

Accioly MT, Pacheco P, Maya-Monteiro CM, Carrossini N, Robbs BK, Oliveira SS et al. Lipid bodies are reservoirs of cyclooxygenase-2 and sites of prostaglandin-E2 synthesis in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 1732–1740.

Yue S, Li J, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Shao T, Song B et al. Cholesteryl ester accumulation induced by PTEN loss and PI3K/AKT activation underlies human prostate cancer aggressiveness. Cell Metab 2014; 19: 393–406.

Guillaumond F, Bidaut G, Ouaissi M, Servais S, Gouirand V, Olivares O et al. Cholesterol uptake disruption, in association with chemotherapy, is a promising combined metabolic therapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 2473–2478.

Bozza PT, Viola JP . Lipid droplets in inflammation and cancer. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2010; 82: 243–250.

de Gonzalo-Calvo D, Lopez-Vilaro L, Nasarre L, Perez-Olabarria M, Vazquez T, Escuin D et al. Intratumor cholesteryl ester accumulation is associated with human breast cancer proliferation and aggressive potential: a molecular and clinicopathological study. BMC Cancer 2015; 15: 460.

Abramczyk H, Surmacki J, Kopec M, Olejnik AK, Lubecka-Pietruszewska K, Fabianowska-Majewska K . The role of lipid droplets and adipocytes in cancer. Raman imaging of cell cultures: MCF10A, MCF7, and MDA-MB-231 compared to adipocytes in cancerous human breast tissue. Analyst 2015; 140: 2224–2235.

Tirinato L, Liberale C, Di Franco S, Candeloro P, Benfante A, La Rocca R et al. Lipid droplets: a new player in colorectal cancer stem cells unveiled by spectroscopic imaging. Stem Cells 2015; 33: 35–44.

El-Mashtoly SF, Yosef HK, Petersen D, Mavarani L, Maghnouj A, Hahn S et al. Label-free Raman spectroscopic imaging monitors the integral physiologically relevant drug responses in cancer cells. Anal Chem 2015; 87: 7297–7304.

Steuwe C, Patel II, Ul-Hasan M, Schreiner A, Boren J, Brindle KM et al. CARS based label-free assay for assessment of drugs by monitoring lipid droplets in tumour cells. J Biophotonics 2014; 7: 906–913.

Daniels VW, Smans K, Royaux I, Chypre M, Swinnen JV, Zaidi N . Cancer cells differentially activate and thrive on de novo lipid synthesis pathways in a low-lipid environment. PLoS One 2014; 9: e106913.

Kamphorst JJ, Cross JR, Fan J, de Stanchina E, Mathew R, White EP et al. Hypoxic and Ras-transformed cells support growth by scavenging unsaturated fatty acids from lysophospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 8882–8887.

Raynor A, Jantscheff P, Ross T, Schlesinger M, Wilde M, Haasis S et al. Saturated and mono-unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholine metabolism in tumour cells: a potential therapeutic target for preventing metastases. Lipids Health Dis 2015; 14: 69.

Liu Y, Zuckier LS, Ghesani NV . Dominant uptake of fatty acid over glucose by prostate cells: a potential new diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Anticancer Res 2010; 30: 369–374.

Caro P, Kishan AU, Norberg E, Stanley IA, Chapuy B, Ficarro SB et al. Metabolic signatures uncover distinct targets in molecular subsets of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell 2012; 22: 547–560.

Li J, Cheng JX . Direct visualization of de novo lipogenesis in single living cells. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 6807.

Rysman E, Brusselmans K, Scheys K, Timmermans L, Derua R, Munck S et al. De novo lipogenesis protects cancer cells from free radicals and chemotherapeutics by promoting membrane lipid saturation. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 8117–8126.

Staubach S, Hanisch FG . Lipid rafts: signaling and sorting platforms of cells and their roles in cancer. Expert Rev Proteomics 2011; 8: 263–277.

Kunkel GT, Maceyka M, Milstien S, Spiegel S . Targeting the sphingosine-1-phosphate axis in cancer, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013; 12: 688–702.

Wang D, Dubois RN . Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2010; 10: 181–193.

Nakanishi M, Rosenberg DW . Multifaceted roles of PGE2 in inflammation and cancer. Semin Immunopathol 2013; 35: 123–137.

Menendez JA, Lupu R . Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 763–777.

Zaidi N, Swinnen JV, Smans K . ATP-citrate lyase: a key player in cancer metabolism. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 3709–3714.

Kuhajda FP . Fatty acid synthase and cancer: new application of an old pathway. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 5977–5980.

Biswas S, Lunec J, Bartlett K . Non-glucose metabolism in cancer cells—is it all in the fat? Cancer Metastasis Rev 2012; 31: 689–698.

Zaugg K, Yao Y, Reilly PT, Kannan K, Kiarash R, Mason J et al. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C promotes cell survival and tumor growth under conditions of metabolic stress. Genes Dev 2011; 25: 1041–1051.

Ricciardi MR, Mirabilii S, Allegretti M, Licchetta R, Calarco A, Torrisi MR et al. Targeting the leukemia cell metabolism by the CPT1a inhibition: functional preclinical effects in leukemias. Blood 2015; 126: 1925–1929.

Reilly PT, Mak TW . Molecular pathways: tumor cells Co-opt the brain-specific metabolism gene CPT1C to promote survival. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 5850–5855.

Sanchez-Macedo N, Feng J, Faubert B, Chang N, Elia A, Rushing EJ et al. Depletion of the novel p53-target gene carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C delays tumor growth in the neurofibromatosis type I tumor model. Cell Death Differ 2013; 20: 659–668.

Samudio I, Harmancey R, Fiegl M, Kantarjian H, Konopleva M, Korchin B et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of fatty acid oxidation sensitizes human leukemia cells to apoptosis induction. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 142–156.

Hernlund E, Ihrlund LS, Khan O, Ates YO, Linder S, Panaretakis T et al. Potentiation of chemotherapeutic drugs by energy metabolism inhibitors 2-deoxyglucose and etomoxir. Int J Cancer 2008; 123: 476–483.

Schlaepfer IR, Rider L, Rodrigues LU, Gijon MA, Pac CT, Romero L et al. Lipid catabolism via CPT1 as a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2014; 13: 2361–2371.

Vargas T, Moreno-Rubio J, Herranz J, Cejas P, Molina S, Gonzalez-Vallinas M et al. ColoLipidGene: signature of lipid metabolism-related genes to predict prognosis in stage-II colon cancer patients. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 7348–7363.

Loizides-Mangold U . On the future of mass-spectrometry-based lipidomics. FEBS J 2013; 280: 2817–2829.

Le TT, Yue S, Cheng JX . Shedding new light on lipid biology with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. J Lipid Res 2010; 51: 3091–3102.

Hilvo M, Denkert C, Lehtinen L, Muller B, Brockmoller S, Seppanen-Laakso T et al. Novel theranostic opportunities offered by characterization of altered membrane lipid metabolism in breast cancer progression. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 3236–3245.

Guenther S, Muirhead LJ, Speller AV, Golf O, Strittmatter N, Ramakrishnan R et al. Spatially resolved metabolic phenotyping of breast cancer by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Cancer Res 2015; 75: 1828–1837.

Ollila S, Hyvonen MT, Vattulainen I . Polyunsaturation in lipid membranes: dynamic properties and lateral pressure profiles. J Phys Chem B 2007; 111: 3139–3150.

Kawashima M, Iwamoto N, Kawaguchi-Sakita N, Sugimoto M, Ueno T, Mikami Y et al. High-resolution imaging mass spectrometry reveals detailed spatial distribution of phosphatidylinositols in human breast cancer. Cancer Sci 2013; 104: 1372–1379.

Eberlin LS, Gabay M, Fan AC, Gouw AM, Tibshirani RJ, Felsher DW et al. Alteration of the lipid profile in lymphomas induced by MYC overexpression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 10450–10455.

Perry RH, Bellovin DI, Shroff EH, Ismail AI, Zabuawala T, Felsher DW et al. Characterization of MYC-induced tumorigenesis by in situ lipid profiling. Anal Chem 2013; 85: 4259–4262.

Shroff EH, Eberlin LS, Dang VM, Gouw AM, Gabay M, Adam SJ et al. MYC oncogene overexpression drives renal cell carcinoma in a mouse model through glutamine metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 6539–6544.

Kiebish MA, Han X, Cheng H, Chuang JH, Seyfried TN . Cardiolipin and electron transport chain abnormalities in mouse brain tumor mitochondria: lipidomic evidence supporting the Warburg theory of cancer. J Lipid Res 2008; 49: 2545–2556.

Lingwood D, Simons K . Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 2010; 327: 46–50.

Mollinedo F, Gajate C . Lipid rafts as major platforms for signaling regulation in cancer. Adv Biol Regul 2015; 57: 130–146.

Lucken-Ardjomande S, Montessuit S, Martinou JC . Bax activation and stress-induced apoptosis delayed by the accumulation of cholesterol in mitochondrial membranes. Cell Death Differ 2008; 15: 484–493.

Dessi S, Batetta B, Pulisci D, Spano O, Anchisi C, Tessitore L et al. Cholesterol content in tumor tissues is inversely associated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in serum in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer 1994; 73: 253–258.

Kolanjiappan K, Ramachandran CR, Manoharan S . Biochemical changes in tumor tissues of oral cancer patients. Clin Biochem 2003; 36: 61–65.

Montero J, Morales A, Llacuna L, Lluis JM, Terrones O, Basanez G et al. Mitochondrial cholesterol contributes to chemotherapy resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 5246–5256.

Li YC, Park MJ, Ye SK, Kim CW, Kim YN . Elevated levels of cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in cancer cells are correlated with apoptosis sensitivity induced by cholesterol-depleting agents. Am J Pathol 2006; 168: 1107–1118; quiz 1404-5.

Llorente A, Skotland T, Sylvanne T, Kauhanen D, Rog T, Orlowski et al. Molecular lipidomics of exosomes released by PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1831: 1302–1309.

Hill MM, Feng J, Hemmings BA . Identification of a plasma membrane Raft-associated PKB Ser473 kinase activity that is distinct from ILK and PDK1. Curr Biol 2002; 12: 1251–1255.

Adam RM, Mukhopadhyay NK, Kim J, Di Vizio D, Cinar B, Boucher K et al. Cholesterol sensitivity of endogenous and myristoylated Akt. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 6238–6246.

Courtney KD, Corcoran RB, Engelman JA . The PI3K pathway as drug target in human cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1075–1083.

Shukla S, Maclennan GT, Hartman DJ, Fu P, Resnick MI, Gupta S . Activation of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway promotes prostate cancer cell invasion. Int J Cancer 2007; 121: 1424–1432.

Borradaile NM, Han X, Harp JD, Gale SE, Ory DS, Schaffer JE . Disruption of endoplasmic reticulum structure and integrity in lipotoxic cell death. J Lipid Res 2006; 47: 2726–2737.

Zhuang L, Kim J, Adam RM, Solomon KR, Freeman MR . Cholesterol targeting alters lipid raft composition and cell survival in prostate cancer cells and xenografts. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 959–968.

Fedida-Metula S, Elhyany S, Tsory S, Segal S, Hershfinkel M, Sekler I et al. Targeting lipid rafts inhibits protein kinase B by disrupting calcium homeostasis and attenuates malignant properties of melanoma cells. Carcinogenesis 2008; 29: 1546–1554.

Wang R, Bi J, Ampah KK, Zhang C, Li Z, Jiao Y et al. Lipid raft regulates the initial spreading of melanoma A375 cells by modulating beta1 integrin clustering. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013; 45: 1679–1689.

Jeon JH, Kim SK, Kim HJ, Chang J, Ahn CM, Chang YS . Lipid raft modulation inhibits NSCLC cell migration through delocalization of the focal adhesion complex. Lung Cancer 2010; 69: 165–171.

Wang J, He L, Combs CA, Roderiquez G, Norcross MA . Dimerization of CXCR4 in living malignant cells: control of cell migration by a synthetic peptide that reduces homologous CXCR4 interactions. Mol Cancer Ther 2006; 5: 2474–2483.

Song JH, Tse MC, Bellail A, Phuphanich S, Khuri F, Kneteman NM et al. Lipid rafts and nonrafts mediate tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand induced apoptotic and nonapoptotic signals in non small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 6946–6955.

Delmas D, Rebe C, Micheau O, Athias A, Gambert P, Grazide S et al. Redistribution of CD95, DR4 and DR5 in rafts accounts for the synergistic toxicity of resveratrol and death receptor ligands in colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2004; 23: 8979–8986.

Kato H, Nishitoh H . Stress responses from the endoplasmic reticulum in cancer. Front Oncol 2015; 5: 93.

Mylonis I, Sembongi H, Befani C, Liakos P, Siniossoglou S, Simos G . Hypoxia causes triglyceride accumulation by HIF-1-mediated stimulation of lipin 1 expression. J Cell Sci 2012; 125: 3485–3493.

Volmer R, van der Ploeg K, Ron D . Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 4628–4633.

Kitai Y, Ariyama H, Kono N, Oikawa D, Iwawaki T, Arai H . Membrane lipid saturation activates IRE1alpha without inducing clustering. Genes Cells 2013; 18: 798–809.

Ariyama H, Kono N, Matsuda S, Inoue T, Arai H . Decrease in membrane phospholipid unsaturation induces unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 22027–22035.

Griffiths B, Lewis CA, Bensaad K, Ros S, Zhang Q, Ferber EC et al. Sterol regulatory element binding protein-dependent regulation of lipid synthesis supports cell survival and tumor growth. Cancer Metab 2013; 1: 3.

Williams KJ, Argus JP, Zhu Y, Wilks MQ, Marbois BN, York AG et al. An essential requirement for the SCAP/SREBP signaling axis to protect cancer cells from lipotoxicity. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 2850–2862.

Rios-Marco P, Martin-Fernandez M, Soria-Bretones I, Rios A, Carrasco MP, Marco C . Alkylphospholipids deregulate cholesterol metabolism and induce cell-cycle arrest and autophagy in U-87 MG glioblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1831: 1322–1334.

Rios-Marco P, Rios A, Jimenez-Lopez JM, Carrasco MP, Marco C . Cholesterol homeostasis and autophagic flux in perifosine-treated human hepatoblastoma HepG2 and glioblastoma U-87 MG cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol 2015; 96: 10–19.

Sbiera S, Leich E, Liebisch G, Sbiera I, Schirbel A, Wiemer L et al. Mitotane inhibits Sterol-O-Acyl Transferase 1 triggering lipid-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in adrenocortical carcinoma cells. Endocrinology 2015; 156: 3895–3908 en20151367.

Ponnusamy S, Meyers-Needham M, Senkal CE, Saddoughi SA, Sentelle D, Selvam SP et al. Sphingolipids and cancer: ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in the regulation of cell death and drug resistance. Future Oncol 2010; 6: 1603–1624.

Henry B, Moller C, Dimanche-Boitrel MT, Gulbins E, Becker KA . Targeting the ceramide system in cancer. Cancer Lett 2013; 332: 286–294.

Carracedo A, Gironella M, Lorente M, Garcia S, Guzman M, Velasco G et al. Cannabinoids induce apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 6748–6755.

Carracedo A, Lorente M, Egia A, Blazquez C, Garcia S, Giroux V et al. The stress-regulated protein p8 mediates cannabinoid-induced apoptosis of tumor cells. Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 301–312.

Salazar M, Carracedo A, Salanueva IJ, Hernandez-Tiedra S, Lorente M, Egia et al. Cannabinoid action induces autophagy-mediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells. J Clin Invest 2009; 119: 1359–1372.

Mehta S, Blackinton D, Omar I, Kouttab N, Myrick D, Klostergaard J et al. Combined cytotoxic action of paclitaxel and ceramide against the human Tu138 head and neck squamous carcinoma cell line. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000; 46: 85–92.

Senkal CE, Ponnusamy S, Rossi MJ, Bialewski J, Sinha D, Jiang JC et al. Role of human longevity assurance gene 1 and C18-ceramide in chemotherapy-induced cell death in human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6: 712–722.

Liu Z, Xia Y, Li B, Xu H, Wang C, Liu Y et al. Induction of ER stress-mediated apoptosis by ceramide via disruption of ER Ca(2+) homeostasis in human adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Cell Biosci 2014; 4: 71.

Hanahan D, Coussens LM . Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2012; 21: 309–322.

Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, Ladanyi A, Buell-Gutbrod R, Zillhardt MR et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med 2011; 17: 1498–1503.

Gazi E, Gardner P, Lockyer NP, Hart CA, Brown MD, Clarke NW . Direct evidence of lipid translocation between adipocytes and prostate cancer cells with imaging FTIR microspectroscopy. J Lipid Res 2007; 48: 1846–1856.

Palm W, Park Y, Wright K, Pavlova NN, Tuveson DA, Thompson CB . The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1. Cell 2015; 162: 259–270.

Commisso C, Davidson SM, Soydaner-Azeloglu RG, Parker SJ, Kamphorst JJ, Hackett S et al. Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature 2013; 497: 633–637.

Record M, Carayon K, Poirot M, Silvente-Poirot S . Exosomes as new vesicular lipid transporters involved in cell-cell communication and various pathophysiologies. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1841: 108–120.

Subra C, Grand D, Laulagnier K, Stella A, Lambeau G, Paillasse M et al. Exosomes account for vesicle-mediated transcellular transport of activatable phospholipases and prostaglandins. J Lipid Res 2010; 51: 2105–2120.

Beloribi S, Ristorcelli E, Breuzard G, Silvy F, Bertrand-Michel J, Beraud E et al. Exosomal lipids impact notch signaling and induce death of human pancreatic tumoral SOJ-6 cells. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e47480.

Xiang X, Poliakov A, Liu C, Liu Y, Deng ZB, Wang J et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 2621–2633.

Sinha P, Clements VK, Fulton AM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S . Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 4507–4513.

Heusinkveld M, de Vos van Steenwijk PJ, Goedemans R, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Gorter A, Welters MJ et al. M2 macrophages induced by prostaglandin E2 and IL-6 from cervical carcinoma are switched to activated M1 macrophages by CD4+ Th1 cells. J Immunol 2011; 187: 1157–1165.

Chang SH, Liu CH, Conway R, Han DK, Nithipatikom K, Trifan OC et al. Role of prostaglandin E2-dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2-induced breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 591–596.

Chu J, Lloyd FL, Trifan OC, Knapp B, Rizzo MT . Potential involvement of the cyclooxygenase-2 pathway in the regulation of tumor-associated angiogenesis and growth in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2003; 2: 1–7.

Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S, Sawaoka H, Hori M, DuBois RN . Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell 1998; 93: 705–716.

Chen JY, Li CF, Kuo CC, Tsai KK, Hou MF, Hung WC . Cancer/stroma interplay via cyclooxygenase-2 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase promotes breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res 2014; 16: 410.

Visentin B, Vekich JA, Sibbald BJ, Cavalli AL, Moreno KM, Matteo RG et al. Validation of an anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate antibody as a potential therapeutic in reducing growth, invasion, and angiogenesis in multiple tumor lineages. Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 225–238.

LaMontagne K, Littlewood-Evans A, Schnell C, O'Reilly T, Wyder L, Sanchez T et al. Antagonism of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors by FTY720 inhibits angiogenesis and tumor vascularization. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 221–231.

Anelli V, Gault CR, Snider AJ, Obeid LM . Role of sphingosine kinase-1 in paracrine/transcellular angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in vitro. FASEB J 2010; 24: 2727–2738.

Flavin R, Peluso S, Nguyen PL, Loda M . Fatty acid synthase as a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Future Oncol 2010; 6: 551–562.

Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Bauer DE, Andreadis C, Shaw AN, Dhanak D et al. ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell 2005; 8: 311–321.

Li S, Qiu L, Wu B, Shen H, Zhu J, Zhou L et al. TOFA suppresses ovarian cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Med Rep 2013; 8: 373–378.

Bovenga F, Sabba C, Moschetta A . Uncoupling nuclear receptor LXR and cholesterol metabolism in cancer. Cell Metab 2015; 21: 517–526.

Flaveny CA, Griffett K, El-Gendy Bel D, Kazantzis M, Sengupta M, Amelio AL et al. Broad anti-tumor activity of a small molecule that selectively targets the Warburg effect and lipogenesis. Cancer Cell 2015; 28: 42–56.

Uto Y . Recent progress in the discovery and development of stearoyl CoA desaturase inhibitors. Chem Phys Lipids (e-pub ahead of print 3 September 2015; doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.08.018).

Graeser R, Bornmann C, Esser N, Ziroli V, Jantscheff P, Unger C et al. Antimetastatic effects of liposomal gemcitabine and empty liposomes in an orthotopic mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2009; 38: 330–337.

Maione F, Oliaro-Bosso S, Meda C, Di Nicolantonio F, Bussolino F, Balliano G et al. The cholesterol biosynthesis enzyme oxidosqualene cyclase is a new target to impair tumour angiogenesis and metastasis dissemination. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 9054.

Clendening JW, Penn LZ . Targeting tumor cell metabolism with statins. Oncogene 2012; 31: 4967–4978.

Pisanti S, Picardi P, Ciaglia E, D'Alessandro A, Bifulco M . Novel prospects of statins as therapeutic agents in cancer. Pharmacol Res 2014; 88: 84–98.

Grosse PY, Bressolle F, Pinguet F . Antiproliferative effect of methyl-beta-cyclodextrin in vitro and in human tumour xenografted athymic nude mice. Br J Cancer 1998; 78: 1165–1169.

Mohammad N, Malvi P, Meena AS, Singh SV, Chaube B, Vannuruswamy G et al. Cholesterol depletion by methyl-beta-cyclodextrin augments tamoxifen induced cell death by enhancing its uptake in melanoma. Mol Cancer 2014; 13: 204.

Pommier AJ, Alves G, Viennois E, Bernard S, Communal Y, Sion B et al. Liver X Receptor activation downregulates AKT survival signaling in lipid rafts and induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2010; 29: 2712–2723.

Guo D, Reinitz F, Youssef M, Hong C, Nathanson D, Akhavan D et al. An LXR agonist promotes glioblastoma cell death through inhibition of an EGFR/AKT/SREBP-1/LDLR-dependent pathway. Cancer Discov 2011; 1: 442–456.

Brusselmans K, Timmermans L, Van de Sande T, Van Veldhoven PP, Guan G, Shechter I et al. Squalene synthase, a determinant of Raft-associated cholesterol and modulator of cancer cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 18777–18785.

Gajate C, Gonzalez-Camacho F, Mollinedo F . Involvement of raft aggregates enriched in Fas/CD95 death-inducing signaling complex in the antileukemic action of edelfosine in Jurkat cells. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e5044.

Gajate C, Mollinedo F . Edelfosine and perifosine induce selective apoptosis in multiple myeloma by recruitment of death receptors and downstream signaling molecules into lipid rafts. Blood 2007; 109: 711–719.

Reis-Sobreiro M, Gajate C, Mollinedo F . Involvement of mitochondria and recruitment of Fas/CD95 signaling in lipid rafts in resveratrol-mediated antimyeloma and antileukemia actions. Oncogene 2009; 28: 3221–3234.

Xu ZX, Ding T, Haridas V, Connolly F, Gutterman JU . Avicin D, a plant triterpenoid, induces cell apoptosis by recruitment of Fas and downstream signaling molecules into lipid rafts. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e8532.

Guan M, Fousek K, Jiang C, Guo S, Synold T, Xi B et al. Nelfinavir induces liposarcoma apoptosis through inhibition of regulated intramembrane proteolysis of SREBP-1 and ATF6. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 1796–1806.

Guan M, Su L, Yuan YC, Li H, Chow WA . Nelfinavir and nelfinavir analogs block site-2 protease cleavage to inhibit castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 9698.

Koltai T . Nelfinavir and other protease inhibitors in cancer: mechanisms involved in anticancer activity. F1000Res 2015; 4: 9.

Little JL, Wheeler FB, Fels DR, Koumenis C, Kridel SJ . Inhibition of fatty acid synthase induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in tumor cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 1262–1269.

von Roemeling CA, Marlow LA, Wei JJ, Cooper SJ, Caulfield TR, Wu K et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 is a novel molecular therapeutic target for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19: 2368–2380.

Obeng EA, Carlson LM, Gutman DM, Harrington WJ Jr., Lee KP, Boise LH . Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood 2006; 107: 4907–4916.

Sarfaraz S, Adhami VM, Syed DN, Afaq F, Mukhtar H . Cannabinoids for cancer treatment: progress and promise. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 339–342.

Torres S, Lorente M, Rodriguez-Fornes F, Hernandez-Tiedra S, Salazar M, Garcia-Taboada E et al. A combined preclinical therapy of cannabinoids and temozolomide against glioma. Mol Cancer Ther 2011; 10: 90–103.

Wang D, Dubois RN . The role of COX-2 in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Oncogene 2010; 29: 781–788.

Xu L, Stevens J, Hilton MB, Seaman S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD et al. COX-2 inhibition potentiates antiangiogenic cancer therapy and prevents metastasis in preclinical models. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 242ra84.

Kurtova AV, Xiao J, Mo Q, Pazhanisamy S, Krasnow R, Lerner SP et al. Blocking PGE2-induced tumour repopulation abrogates bladder cancer chemoresistance. Nature 2015; 517: 209–213.

Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Sato K, Chan JA, Niedzwiecki D et al. Aspirin and COX-2 inhibitor use in patients with stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107: 345.

Thill M, Reichert K, Woeste A, Polack S, Fischer D, Hoellen F et al. Combined treatment of breast cancer cell lines with vitamin D and COX-2 inhibitors. Anticancer Res 2015; 35: 1189–1195.

Knab LM, Grippo PJ, Bentrem DJ . Involvement of eicosanoids in the pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer: the roles of cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 10729–10739.

Kim SH, Margalit O, Katoh H, Wang D, Wu H, Xia D et al. CG100649, a novel COX-2 inhibitor, inhibits colorectal adenoma and carcinoma growth in mouse models. Invest New Drugs 2014; 32: 1105–1112.

Nagahashi M, Ramachandran S, Kim EY, Allegood JC, Rashid OM, Yamada et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase 1 promotes breast cancer progression by stimulating angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 726–735.

Liang J, Nagahashi M, Kim EY, Harikumar KB, Yamada A, Huang WC et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate links persistent STAT3 activation, chronic intestinal inflammation, and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell 2013; 23: 107–120.

Zhang L, Wang X, Bullock AJ, Callea M, Shah H, Song J et al. Anti-S1P antibody as a novel therapeutic strategy for VEGFR TKI-resistant renal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 1925–1934.

Pachioni Jde A, Magalhães JG, Lima EJ, Bueno Lde M, Barbosa JF, de Sá MM et al. Alkylphospholipids - a promising class of chemotherapeutic agents with a broad pharmacological spectrum. Pharm Pharm Sci 2013; 16: 742–759.

Wang H, Haridas V, Gutterman JU, Xu ZX . Natural triterpenoid avicins selectively induce tumor cell death. Commun Integr Biol 2010; 3: 205–208.

Tomé-Carneiro J, Larrosa M, González-Sarrías A, Tomás-Barberán FA, García-Conesa MT, Espín JC . Resveratrol and clinical trials: the crossroad from in vitro studies to human evidence. Curr Pharm Des 2013; 19: 6064–6093.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Oncogenesis is an open-access journal published by Nature Publishing Group. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Beloribi-Djefaflia, S., Vasseur, S. & Guillaumond, F. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 5, e189 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/oncsis.2015.49

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/oncsis.2015.49

This article is cited by

-

HIF-2α/LINC02609/APOL1-mediated lipid storage promotes endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and regulates tumor progression in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2024)

-

White adipocyte dysfunction and obesity-associated pathologies in humans

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2024)

-

Emerging role of lipophagy in liver disorders

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2024)

-

The oncogenic circular RNA circ_63706 is a potential therapeutic target in sonic hedgehog-subtype childhood medulloblastomas

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2023)

-

Clinical features and lipid metabolism genes as potential biomarkers in advanced lung cancer

BMC Cancer (2023)