The Natural History of Model Organisms: Nothobranchius furzeri, an 'instant' fish from an ephemeral habitat

- Article

- Figures and data

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Natural life cycle and longevity

- Distribution

- Male colour morphs

- Genetic structure

- Diet

- Biotic interactions

- Reproduction and mating behaviour

- Embryo ecology

- Key advantages of N. furzeri for the model species role

- Conclusions

- References

- Decision letter

- Author response

- Article and author information

- Metrics

Abstract

The turquoise killifish, Nothobranchius furzeri, is a promising vertebrate model in ageing research and an emerging model organism in genomics, regenerative medicine, developmental biology and ecotoxicology. Its lifestyle is adapted to the ephemeral nature of shallow pools on the African savannah. Its rapid and short active life commences when rains fill the pool: fish hatch, grow rapidly and mature in as few as two weeks, and then reproduce daily until the pool dries out. Its embryos then become inactive, encased in the dry sediment and protected from the harsh environment until the rains return. This invertebrate-like life cycle (short active phase and long developmental arrest) combined with a vertebrate body plan provide the ideal attributes for a laboratory animal.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41548.001Introduction

The African savannah is dotted with ephemeral freshwater pools known as water pans, which form during the rainy season. Killifishes of the genus Nothobranchius, colloquially called annual fishes, have adapted to live in these pools. Popular with specialist aquarium hobbyists for their stunning colouration, most of 75 described species are available in captivity (Neumann, 2008), which is how Nothobranchius furzeri first made its way into research laboratories worldwide. Alessandro Cellerino, a physiologist from Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy, was intrigued by an incredibly short-lived population of the annual fish that his friend Stefano Valdesalici bred at home. Experimental investigation of its lifespan revealed that the fish matured after just four weeks, after which their mortality increased sharply from the age of six weeks and all the fish died within 10 weeks (Valdesalici and Cellerino, 2003). The fish of this strain were named GRZ after Gona Re Zhou National Park in Zimbabwe where the fish were originally collected in 1970 (Jubb, 1971). They were later found to live slightly longer as housing conditions developed (Cellerino et al., 2016), though it remains the shortest-lived population of N. furzeri yet recorded. Collection trips to Mozambique and Zimbabwe between 2004 and 2016 assembled a set of populations that vary in lifespan and possess a variable level of inbreeding (Terzibasi et al., 2008; Cellerino et al., 2016; Reichard et al., 2017a).

The remarkably short lifespan of N. furzeri recapitulates the hallmarks of vertebrate ageing (Harel et al., 2015), condensed into few weeks and responsive to pharmacological, dietary and lifestyle interventions (Cellerino et al., 2016). Its genome has been sequenced and assembled (Valenzano et al., 2015; Reichwald et al., 2015), and there are transcriptomes for a number of its tissues (Petzold et al., 2013; Baumgart et al., 2014; Baumgart et al., 2017). Several inbred lines are also available (Hu and Brunet, 2018) and genome-editing techniques are widely adopted to rapidly produce stable transgenic lines too (Harel et al., 2016). With this background, N. furzeri has reached outside the world of ageing research and has become valuable for studies in such disparate branches of investigation as evolutionary genomics (Reichwald et al., 2015), regenerative medicine (Wendler et al., 2015), developmental biology (Hu and Brunet, 2018) and ecotoxicology (Philippe et al., 2018). Here, we explore how our understanding of the natural history of the species makes a key contribution to the development of this species as a laboratory model.

Natural life cycle and longevity

The life cycle of N. furzeri is adapted to the transient nature of its habitat and is strictly separated into two distinct phases. The first phase starts when fish hatch after their pool is inundated with rainwater and immediately start feeding. Explosive juvenile growth brings them to sexual maturity in as little as two weeks, growing from the initial size of 5 mm to 30–50 mm over that period (Vrtílek et al., 2018a). Growth slows thereafter as resources are diverted to reproduction, but a body size of 75 mm can be reached in males after 10–15 weeks (Blažek et al., 2013; Vrtílek et al., 2018a). Importantly, their growth rate is strongly dependent on population density and food availability; fish in dense populations are typically small and sexually immature at an age of 3–5 weeks, both in the wild and in the laboratory (Graf et al., 2010; Grégoir et al., 2018; Philippe et al., 2018; Vrtílek et al., 2018a). Individual fish vary in growth rates (Blažek et al., 2013), perhaps reflecting variation in personality traits (Thoré et al., 2018). Upon sexual maturity, females lay eggs daily. A typical fecundity of 20–120 eggs per day was estimated in wild populations, with more variation among populations than among females within a sample (Vrtílek and Reichard, 2016; Vrtílek et al., 2018b), seemingly in response to resource availability.

All adult fish die when their pool desiccates, but mortality is strong over the entire lifespan (Vrtílek et al., 2018c). In longer-lasting pools (persisting more than four months), fish often disappear despite the habitat still appearing capable of supporting them. The fish likely succumb to a combination of predation by birds, bouts of extremely high water temperatures, decreased water quality from organic input by visiting animals, low dissolved oxygen levels, exhaustion of resources, and physiological deterioration as a trade-off to rapid juvenile development (Reichard, 2015). While wild-derived, outbred N. furzeri populations have a maximum lifespan (defined as 90% survival at the population level) of 25–42 weeks in captivity (Terzibasi et al., 2008; Tozzini et al., 2013; Blažek et al., 2017), only one of 13 N. furzeri populations monitored in the wild survived beyond the age of 17 weeks and most disappeared at the age of 3–10 weeks as their habitat dried up (Vrtílek et al., 2018c). After desiccation, dry sediment retains the eggs in a dormant state (diapause); an adaptation to the harsh environmental conditions, over the entire dry season that lasts 5–11 months (Cellerino et al., 2016; Vrtílek et al., 2018b).

Distribution

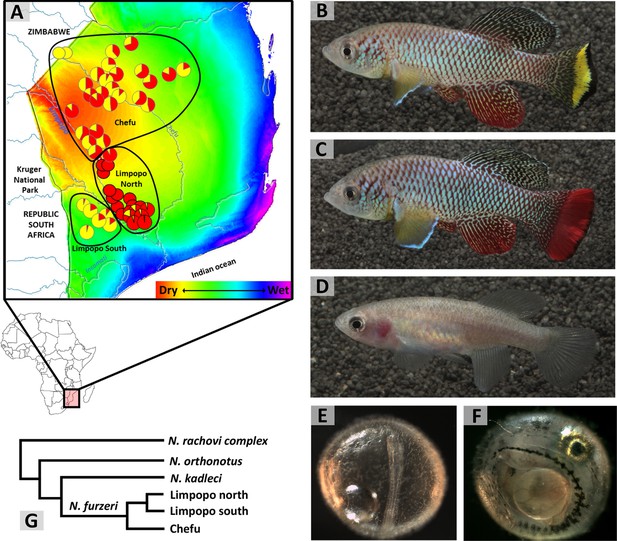

N. furzeri is distributed in southern Mozambique, with a few populations extending to adjacent parts of southern Zimbabwe, only few kilometres across the border (Figure 1A). Interestingly, the range of N. furzeri lies on a gradient in aridity associated with distance from the coast. Evaporation, the amount of rainfall and its predictability are major environmental factors that vary across that gradient (Terzibasi et al., 2008; Tozzini et al., 2013; Polačik et al., 2018), with the driest and least predictable conditions furthest from the ocean (and at the highest altitude) (Figure 1A). N. furzeri is absent in the wettest region, where another two Nothobranchius species, that otherwise coexist with N. furzeri, maintain viable populations. In contrast, N. furzeri is the most common Nothobranchius species in the dry region, 90–400 km from the coast and 19–220 m above sea level (Reichard et al., 2017a). Two isolated Zimbabwean populations are found even higher, at 325–340 m above sea level. To date, we have located and georeferenced 90 N. furzeri populations over its entire range and their geographic coordinates are accessible at the Figshare repository (doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7017167). Our sampling was limited by accessibility from roads and there are many more N. furzeri populations scattered throughout the Mozambican mopane and miombo woodlands and Acacia savannah.

Turquoise killifish phenotypes and their distribution.

(A) Map of N. furzeri distribution across its entire range overlaid on a gradient of aridity (wet to dry: blue to red) and with the proportion of male colour morphs visualised by pie charts and the geographic distribution of intra-specific clades delineated by black lines. (B) Adult yellow morph male, (C) red morph male, and (D) female N. furzeri. (E) Embryo at diapause II, representing the longest interval of its lifespan in natural habitats. (F) Embryo at diapause III, fully developed and awaiting hatching cues. (G) Simplified schematic phylogeny of the Southern clade of Nothobranchius, with details on N. furzeri intra-specific lineages (simplified from Bartáková et al., 2015). Image credits: Martin Reichard (1A, 1G), Radim Blažek (1B–1D), Matej Polačik (1E, 1F).

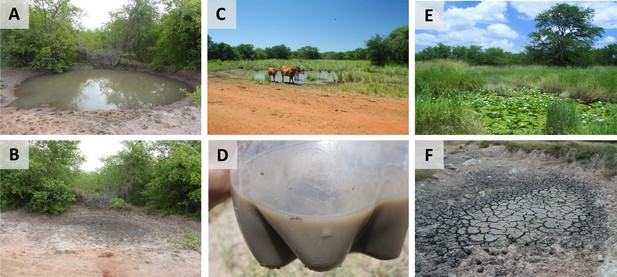

Local pools vary greatly in size and shrink gradually (Vrtílek et al., 2018b) (Figure 2A–B). Environmental conditions in the pool may be harsh; water temperature can fluctuate between 20 and 36°C from early morning to late afternoon (Reichard et al., 2009; Žák et al., 2018). Late in the season (in May), morning water temperature can drop to 15°C. Fine sediment is repeatedly disturbed by cattle (which have functionally replaced the wild African megafauna) (Figure 2C) and partially dissolves in water, producing extremely turbid conditions (Figure 2D). However, in cases when the pool is thickly overgrown with vegetation (Figure 2E) and undisturbed by domestic cattle, the water can be transparent.

Turquoise killifish habitats.

(A) A structurally simple habitat one week after filling with water. (B) The same habitat three weeks after filling, fully desiccated. (C) Domestic cattle that commonly visits killifish habitats. (D) Turbid water from a structurally simple killifish habitat discoloured by dissolved fine sediment particles. (E) A structurally complex habitat with abundant aquatic vegetation. (F) Desiccated pool sediment, with typical deep cracks. Image credits: Milan Vrtílek (2A, 2B), Martin Reichard (2C, 2E, 2F), Matej Polačik (2D).

Male colour morphs

Two distinct colour morphs of male N. furzeri occur, often coexisting in the same population (Reichard et al., 2009). The "yellow" morph (Figure 1B) possesses a yellow crescent marking along the outer margin of the caudal fin, outlined by a black margin. "Red" morph males (Figure 1C) have red caudal fins. The extent of colouration on the caudal fin varies widely among wild populations, but the two morphs are clearly discrete (Valenzano et al., 2009; Ng'oma et al., 2014). The black margin of the caudal fin is also present in some populations of red males and exceptionally absent in yellow males. Female colouration is dull and brownish and shows no indication of polymorphism (Figure 1D).

The geographic distribution of the morphs suggests a link between male colouration and adaptations to different habitat conditions. The yellow morph dominates dry, marginal parts of the range, with exclusively yellow males in the driest region of Zimbabwe. Red males dominate populations in the wet part of the range (Figure 1A) (Reichard et al., 2009; Dorn et al., 2011). This contrast is mirrored in the colouration of the most common laboratory strains, with the short-lived GRZ comprising exclusively yellow males while the longer-lived MZM0403 are exclusively red (Cellerino et al., 2016). Interestingly, most natural populations are polymorphic (Figure 1A) and no differences in life history traits between red and yellow males have been established where they coexist. While it is tempting to associate male colouration with adaptation to dry and wet conditions, there is no evidence of any causal link so far.

Genetic structure

Populations of N. furzeri are divided into two main phylogeographic clades (named Chefu and Limpopo), with limited secondary contact (Terzibasi et al., 2008; Bartáková et al., 2013; Figure 1A). The populations are strongly structured, with rare dispersal between them. The population genetic signature reveals that the Chefu clade has recently experienced dramatic population expansion (Dorn et al., 2011) and demonstrated linkage between populations along the small rivulet basins (Bartáková et al., 2015). Hence, large floods, occurring in exceptionally wet years, are assumed to provide the main mode of dispersal between populations (Reichard, 2015). Surprisingly for a fish, large rivers form boundaries in the distribution of clades and species, including a division of the Limpopo clade to two subclades (Figure 1G) and a boundary between the range of N. furzeri and its sister species, N. kadleci (Bartáková et al., 2015).

Diet

N. furzeri are opportunistic and generalist predators of small invertebrates. In general, the diet reflects prey availability in particular pools. Small crustaceans (Cladocera, Copepoda, and Ostracoda) typically constitute more than 70% of digested prey, with insect larvae also being a common prey item (Polačik and Reichard, 2010). Backswimmers (nothonectid bugs) are common in the pools but underrepresented in the diet. Chironomid larvae, the most common diet of N. furzeri in the laboratory, are also consumed by wild N. furzeri (Polačik and Reichard, 2010). The diet of N. furzeri differs from the two coexisting species (N. orthonotus and N. pienaari) when prey is abundant though all species resort to any available food of a suitable size when choice is limited (Polačik et al., 2014a). The diet is reflected in the intestinal microbiome and wild N. furzeri populations differ in the microbial composition of their guts (Smith et al., 2017). Interestingly, laboratory fish possess the core microbiota of wild N. furzeri and reconstitution of high microbial diversity in old fish extends their lifespan in the laboratory (Smith et al., 2017).

Biotic interactions

Predators

Potential predators include wading and diving birds, such as herons, hammerheads, storks and kingfishers. These birds prey on killifish, tadpoles and, perhaps, larger invertebrates. Large predatory waterbugs are abundant in many pools and readily consume adult killifish in captivity. These sit-and-wait predators may hunt killifish, especially in pools with dense vegetation. Lungfish (Protopterus annectens) commonly coexist with N. furzeri and may also prey on them, though they are not their typical predator (Reichard et al., 2014). The eggs of N. furzeri are likely predated by a range of invertebrates. For instance, freshwater crabs can be abundant in N. furzeri habitats and probably extract killifish eggs from the sediment.

Parasites

The parasites of wild N. furzeri have been well characterised (Nezhybová et al., 2017). All recorded animal parasites were endoparasites, infecting muscles and internal organs. Perhaps most notably, killifish predominantly hosted intermediate stages of the parasites, forming an important link in the transmission cascade to the final hosts: fish-eating birds. The metacercariae larval stage of parasitic trematodes was by far the most abundant parasite, typically with tens of them infecting the muscle tissue. A surprisingly high diversity of flukes (Trematoda), roundworms (Nematoda) and tapeworms (Cestoda) also reside in N. furzeri muscle, intestine, cerebral and abdominal cavities, gallbladder and gills. It is clear that N. furzeri are challenged by a multitude of infections over their short lifespan and capable of encysting parasites that penetrated their bodies, providing a potential to study their immune responses.

One fluke species deserves particular attention. Larvae of Apatemon sp. infect the cerebral cavity (Nezhybová et al., 2017) and manipulate host behaviour. When attacked by a bird, infected killifish stay close to the water surface, even jumping onto water lily pads and thereby exposing themselves to predators. In contrast, uninfected fish quickly seek refuge when exposed to potential predator attack.

Reproduction and mating behaviour

All Nothobranchius species are sexually dimorphic (Sedláček et al., 2014). Male colouration and mating behaviour appear strongly sexually selected (Haas, 1976a). Males compete aggressively for access to females and large males are dominant (Polačik and Reichard, 2009). Females express mate choice by approaching a displaying male. Males actively pursue females and may coerce spawning (Polačik and Reichard, 2011). The elaborate male colouration is puzzling, as N. furzeri often live in extremely turbid water where visibility is minimal. Indeed, male colouration fades in turbid water. Courtship is brief; the male approaches a female and stops to perform lateral displays with his unpaired fins extended. A receptive female allows the male to fold her in his dorsal fin and the female lays an egg into the sediment. During oviposition, the pair jerks and the sediment is disturbed. With the aid of stiffened rays of the anal fin, the egg is deposited slightly into the substrate (Passos et al., 2015). Most eggs are found at pool margins (M. Polačik, unpublished data). There is no consistent choice of red or yellow males by individual N. furzeri females (Reichard and Polačik, unpublished data) and mate choice appears to be based on other traits.

Reproduction occurs primarily in the morning. The eggs are ovulated just after sunrise (07:00-08:00) (Haas, 1976b) and by 10:00 some females have already spawned all their ovulated eggs. Most females are spent by 15:00 and a new batch of eggs is ovulated next morning (Vrtílek and Reichard, 2016). Daily fecundity is strongly contingent upon long-term (the effect of body mass: Vrtílek and Reichard, 2016) and short-term (the effect of ration on the preceding day: Vrtílek and Reichard, 2015) access to resources.

Embryo ecology

The embryonic phase of the N. furzeri life cycle represents the longest but least understood part of the life cycle in the wild. All Nothobranchius populations are limited to pools with a special type of substrate composed of an alkaline swelling clay (Watters, 2009), the physical and chemical properties of which are crucial for the survival of N. furzeri eggs. Annual killifish possess three dormancy stages occurring at defined developmental points (Wourms, 1972) (Box 1). Watters, 2009 proposed a model of natural embryo development of Nothobranchius that links embryo developmental with three phases of incubation conditions (wet, dry and humid) (Box 1).

Box 1.

Embryo development

Embryonic diapause is a distinctive feature of annual fish. It occurs through a developmental arrest coupled with a marked depression in metabolic rate (Podrabsky and Hand, 1999) at three well-defined developmental points called facultative diapauses, all of which can be entered or skipped. Diapause I occurs after an early stage in embryonic development called epiboly, when some cells are distributed across the yolk. It can be induced by a lack of oxygen (anoxia), low temperature and possibly by other conditions (Wourms, 1972). Diapause II occurs in the long embryo, midway through embryo development (at the 38 somite stage; Figure 1E). Some rudimentary organs are visible but the circulatory system is inactive (Wourms, 1972; Podrabsky et al., 2017). At diapause III (Figure 1F), the embryo has completed its development but awaits appropriate hatching cues at a decreased metabolic rate (Podrabsky et al., 2010; Furness et al., 2015a; Furness, 2016). While this developmental pathway appears strikingly congruent across all annual killifish clades (Furness et al., 2015b), it remains to be determined whether it also fully applies to N. furzeri. Watters, 2009 proposed a model of natural embryo development of Nothobranchius that links three embryo developmental phases with the three phases of incubation conditions (wet, dry and humid). During the wet phase, the eggs are deposited into the upper substrate layer. Anoxic conditions in the sediment apparently trigger the onset of diapause I (Watters, 2009). Any embryo development beyond diapause I in aquatic conditions in the wild is rare (Domínguez-Castanedo et al., 2013) and likely linked to embryo position outside the anoxic substrate. The dry incubation phase starts with desiccation (Figure 2B), when the substrate loses its moisture and breaks along deep cracks (Figure 2E). This oxygenates the substrate and embryos resume their development to reach diapause II (Watters, 2009), a stage most resistant to water loss (Podrabsky et al., 2001). The egg banks in dry sediment are exclusively composed of diapause II embryos (Domínguez-Castanedo et al., 2017). Specific physical features of the clay-rich substrate ensure that some moisture is retained even in the upper substrate layer (Watters, 2009). The humid phase starts when the first rains moisten the substrate. Increased moisture and a decrease in oxygen availability supposedly trigger development from diapause II to diapause III (Watters, 2009). Embryos at diapause III await a hatching stimulus that is probably associated with torrential rains and inundation of the pool. Hatching is synchronous within and among populations in years when a cyclone-associated rainfall inundates the pools (Polačik et al., 2011), but may be asynchronous in dry years (Reichard et al., 2017b), perhaps because the substrate is only gradually wetted.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41548.004Large variability in embryo developmental dynamics is a key feature for the long-term persistence of N. furzeri populations in their highly unpredictable environment (Furness, 2016), serving as an effective bet-hedging strategy against false hatching cues, such as insufficient rainfall (Polačik et al., 2017). Erratic rains and mid-season desiccation generate conditions for two (or perhaps even more) generations or cohorts in some years (Reichard et al., 2017b).

Laboratory research in N. furzeri and other annual killifishes has suggested that developmental disparity is achieved through maternal effects, perhaps based on RNA or protein products. Interestingly, embryos of young females tend to develop rapidly while embryos of older females tend to halt development at diapause (Podrabsky et al., 2010; Polačik et al., 2017); a seeming adaptation to the possibility of a second inundation in a single rainy season that the eggs of young females experience more often than the eggs of older females (Polačik et al., 2014b). However, in the wild the beginning and end of diapause, at least in other killifish species, appears to be controlled by environmental factors (Matias and Markofsky, 1978; Podrabsky et al., 2010; Domínguez-Castanedo et al., 2017) and developmental variability may be achieved through habitat heterogeneity rather than intrinsic control. Gradual desiccation and vertical distribution of embryos create a cline of incubation conditions that generate a staggered embryo development.

The course of embryo development has marked impacts on post-hatching lifespan. Rapidly developing embryos produce phenotypes with a rapid post-hatching strategy, typified by a smaller size at hatching but more rapid growth and sexual maturation, and smaller final size and shorter lifespan (Polačik et al., 2014b). It remains to be identified whether embryonic diapause is causally responsible for the limited rapid development later in life, representing one of the outstanding questions to be addressed (Box 2). Intriguingly, in a Neotropical annual killifish, insulin-like growth factor signalling regulates developmental trajectories (Woll and Podrabsky, 2017), representing candidate regulatory pathway for killifish life history.

Box 2.

Outstanding questions about the natural history of N. furzeri

Do N. furzeri senesce in natural populations? In the wild, the life of N. furzeri is often brief but may be longer than four months, especially in wet years. How much do wild N. furzeri suffer from ageing-related declines?

How do N. furzeri embryos develop under natural conditions? Current knowledge of the embryo development comes from laboratory conditions. As incubation in the laboratory largely differs from natural conditions, we need to know how much it diverges from the natural course of development.

Which genes underlie lifespan and ageing? With natural populations that predictably vary in lifespan, can we dissect genetic and regulatory pathways associated with differences in ageing?

Is rapid juvenile development traded off against rapid deterioration later in life? When comparing different Nothobranchius species, it appears so, but no longitudinal study has compared life history traits within a single cohort, be it in the laboratory or in the wild.

Do rapid and slow pace of life coexist within the same N. furzeri populations? There is impressive variability in the speed of juvenile development among individuals within the same pool (and laboratory cohort). Is this variation determined by the individual’s genetic background or primarily affected by environmental and developmental conditions that an individual experiences during early life?

Do regulatory pathways that control diapause and ageing overlap? Regulatory networks associated with growth and development are involved in both diapause and ageing in non-vertebrate models (Frézal and Félix, 2015). Could that link help us to understand the prevention of ageing-associated damage?

What are the sources of persistent male-biased mortality in wild populations? Combining data from wild populations with experiments in the laboratory may elucidate why male N. furzeri, like many other species including humans, die younger than females.

Why do males coexist in two colour morphs? Existence of two male morphs is often associated with discrete reproductive tactics or with speciation through adaptation to a divergent environment or from strong female choice.

Key advantages of N. furzeri for the model species role

The key advantage of N. furzeri as a model species stems from the combination of its rapid post-hatching lifestyle and long phase of embryonic arrest that can be altered by manipulating environmental conditions. Having a model with a vertebrate body plan and invertebrate-like life history and lifespan (i.e. short and rapid active lifespan and dormant stage) is a valuable characteristic beyond the field of ageing research, not least because researchers are often constrained by the duration of grant funding. The arrested stage makes the species ideal for storing and shipping and permits flexible time management when working with this 'instant' fish (Polačik et al., 2016). In addition, given harsh and variable conditions in natural habitats, captive N. furzeri does not require any precise conditions for water quality and housing, perhaps except access to abundant and nutrient rich food (Polačik et al., 2016; Dodzian et al., 2018).

Information on wild N. furzeri populations, and particularly the environmental gradient in its range, have been especially instrumental in explaining differences in lifespan among captive strains (Tozzini et al., 2013; Blažek et al., 2017) and in validating that its rapid life history is not an artefact of the laboratory (Vrtílek et al., 2018a; Vrtílek et al., 2018c). Field studies have also strengthened conclusions on the role of microbiota on ageing (Smith et al., 2017) and genomic insights into the evolution of short lifespan (Valenzano et al., 2015; Reichwald et al., 2015). Formulating a standardised artificial diet that would be readily consumed by captive N. furzeri now appears critical to increase experimental repeatability across laboratories. Detailed understanding of the natural diet of N. furzeri (Polačik and Reichard, 2010; Polačik et al., 2014a) should help the community to accomplish this goal.

Conclusions

Compared to other fish model systems in biomedical research (e.g. Parichy, 2015), our understanding of the natural history of N. furzeri is substantial (Cellerino et al., 2016). Indeed, N. furzeri may, uniquely, be a model that bridges the interests of ecological and biomedical research (Cellerino et al., 2016). Still, we know relatively little about some features of the natural history of N. furzeri. While some pressing issues are outlined in Box 2, we highlight that the greatest gap in our knowledge of the natural life cycle of N. furzeri is in understanding embryonic development under natural conditions. Data from wild populations demonstrated that high phenotypic plasticity of N. furzeri, manifested in the laboratory by individually disparate growth rates, timing of sexual maturation and fecundity, is natural. While perhaps complicating some experimental designs, it raises a multitude of questions on the underlying mechanisms, from gene expression to individual behaviour (Box 2). With much more to be discovered on the natural history of the species, we anticipate that N. furzeri will continue to be instrumental in showing how conceptual and methodological insights from ecological and biomedical research can be integrated within a single research agenda (Reichard et al., 2015; Cellerino et al., 2016).

References

-

Terrestrial fishes: rivers are barriers to gene flow in annual fishes from the African savannaJournal of Biogeography 42:1832–1844.https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12567

-

A protocol for laboratory housing of turquoise killifish (Nothobranchius furzeri)Journal of Visualized Experiments 134:57073.https://doi.org/10.3791/57073

-

First observations of annualism in (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae)Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 24:15–20.

-

Convergent evolution of alternative developmental trajectories associated with diapause in African and South American killifishProceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282:20142189.https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2189

-

A new Nothobranchius (Pisces, Cyprinodontidae) from Southeastern RhodesiaJournal of American Killifish Association 8:12–19.

-

Eierlegende Zahnkarpfen128, Prachtgrunkärpflinge, Eierlegende Zahnkarpfen, Marktheidenfeld, Germany, Schleunungdruck GmbH.

-

BookReproductive behavior and sexual selection in annual fishesIn: Berois N, García G, de Sá R, editors. Annual Fishes: Life History Strategy, Diversity, and Evolution. CRC Press. pp. 207–229.

-

Combined effects of cadmium exposure and temperature on the annual killifish (Nothobranchius furzeri)Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 37:2361–2371.https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4182

-

Survival of water stress in annual fish embryos: dehydration avoidance and egg envelope amyloid fibersAmerican Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 280:R123–R131.https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R123

-

The bioenergetics of embryonic diapause in an annual killifish, Austrofundulus limnaeusJournal of Experimental biology 202:2567–2580.

-

Indirect fitness benefits are not related to male dominance in a killifishBehavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 63:1427–1435.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-009-0798-2

-

Alternative intrapopulation life-history strategies and their trade-offs in an African annual fishJournal of Evolutionary Biology 27:854–865.https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12359

-

Laboratory breeding of the short-lived annual killifish Nothobranchius furzeriNature Protocols 11:1396–1413.https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2016.080

-

Maternal source of variability in the embryo development of an annual killifishJournal of Evolutionary Biology 30:738–749.https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13038

-

Local variation in embryo development rate in annual fishJournal of Fish Biology 92:1359–1370.https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13591

-

BookThe evolutionary ecology of African annual fishesIn: Berois N, García G, de Sá R, editors. Annual Fishes: Life History Strategy, Diversity, and Evolution. CRC Press. pp. 133–158.

-

Hatching date variability in wild populations of four coexisting species of African annual fishesDevelopmental Dynamics 246:827–837.https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.24500

-

Evolution of body colouration in killifishes (Cyprinodontiformes: Aplocheilidae, Nothobranchiidae, Rivulidae): Is male ornamentation constrained by intersexual genetic correlation?Zoologischer Anzeiger - A Journal of Comparative Zoology 253:207–215.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcz.2013.12.004

-

Extremely short lifespan in the annual fish Nothobranchius furzeriProceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 270 Suppl 2:S189–S191.https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0048

-

Highly plastic resource allocation to growth and reproduction in females of an African annual fishEcology of Freshwater Fish 24:616–628.https://doi.org/10.1111/eff.12175

-

Extremely rapid maturation of a wild African annual fishCurrent Biology 28:R822–R824.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.031

-

The ecology and distribution of Nothobranchius fishesThe Journal of the American Killifish Association 42:37–76.

-

Insulin-like growth factor signaling regulates developmental trajectory associated with diapause in embryos of the annual killifish Austrofundulus limnaeusThe Journal of Experimental Biology 220:2777–2786.https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.151373

-

The developmental biology of annual fishes. 3. Pre-embryonic and embryonic diapause of variable duration in the eggs of annual fishesJournal of Experimental Zoology 182:389–414.https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.1401820310

Decision letter

-

Stuart RF KingReviewing Editor; eLife, United Kingdom

-

Peter A RodgersSenior Editor; eLife, United Kingdom

In the interests of transparency, eLife includes the editorial decision letter and accompanying author responses. A lightly edited version of the letter sent to the authors after peer review is shown, indicating the most substantive concerns; minor comments are not usually included.

Thank you for submitting your article "The Natural History of Model Organisms: Nothobranchius furzeri, an 'instant' fish from an ephemeral habitat" for consideration by eLife. Your article has been reviewed by three peer reviewers, and the evaluation has been overseen by two Features Editors at eLife (Stuart King and Peter Rodgers). The following individuals involved in review of your submission have agreed to reveal their identity: Andrew Furness and Dario Riccardo Valenzano.

After a consultation with the reviewers, the editor has drafted this decision to help you prepare a revised submission.

Summary:

This essay is being considered as part of a series of articles on "The Natural History of Model Organisms" (https://elifesciences.org/collections/8de90445/the-natural-history-of-model-organisms). Each article should explain how our knowledge of the natural history of a model organism has informed recent advances in biology, and how understanding its natural history can influence/advance future studies.

This article summarizes what is known of the natural history of the turquoise killifish (Nothobranchius furzeri), an interesting model organism that is gaining traction in several fields of investigation. The manuscript is compelling, clear and easy to read. However, a number of details should be attended to prior to publication.

The editor may also contact you separately about some editorial or stylistic issues that will need to be addressed.

Essential revisions:

1) The sections in the article provide a comprehensive introduction to the natural history of N. furzeri. However, more should be done to address "how our understanding of the natural history of the species makes a key contribution to its development as a laboratory model" (as stated in the Introduction). Please revise the sections to emphasise how knowledge of N. furzeri's natural history has benefited researchers working with this species in the lab, and/or discoveries in specific fields mentioned in the Introduction. This change would help the article to stand out from other recent (and less-recent) general reviews on N. furzeri as a model system in biology (e.g. Terzibasi et al., 2008; Reichard et al., 2015; Cellerino et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2018).

2) Despite the raising interest about N. furzeri by the scientific community, the reviewers felt it was an overstatement to refer to it as "an established vertebrate model in ageing research" and "the species of choice in […] evolutionary genomics, regenerative medicine, developmental biology and ecotoxicology". This text should be toned down. The revised text should aim to give a more balanced view (i.e. pros and cons) of how the natural history of the species contributes to its usefulness as a model organism. (Brief comparisons with other model organisms, including invertebrates and other vertebrates, could be considered to add wider context or strengthen arguments.)

3) Some of the cited work on killifish diapause and reproduction is from species besides N. furzeri; yet the way the references are cited does not make this clear to a reader unfamiliar with the system. Please include a 'disclaimer' somewhere in the text to indicate that what is known about diapause/development is drawn from studies of other related annual killifish, and although many aspects seem to be highly congruent among species, it remains to be determined whether the same applies to N. furzeri specifically.

4) The main text mentions that little is known about the development in the wild. As such, please consider including at least one or two question about the developmental pathways of N. furzeri embryos in the wild into the "Outstanding questions" in Box 2.

5) The paper currently includes 60 references, 28 of which are directly from the two authors. Though the authors have majorly contributed to the development of N. furzeri as a biomedical and ecological system, they should consider if all these citations are needed and if other articles have been missed from the reference list.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41548.008Author response

Essential revisions:

1) The sections in the article provide a comprehensive introduction to the natural history of N. furzeri. However, more should be done to address "how our understanding of the natural history of the species makes a key contribution to its development as a laboratory model" (as stated in the Introduction). Please revise the sections to emphasise how knowledge of N. furzeri's natural history has benefited researchers working with this species in the lab, and/or discoveries in specific fields mentioned in the Introduction. This change would help the article to stand out from other recent (and less-recent) general reviews on N. furzeri as a model system in biology (e.g. Terzibasi et al., 2008; Reichard et al., 2015; Cellerino et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2018).

We entirely agree with that comment. Ironically, we deleted a special paragraph in the “Key advantages” section in the first version of the manuscript during the final pruning of the text. This section is now included (subsection “Key advantages of N. furzeri for the model species role”) and it recapitulates the most instrumental insights that knowledge of natural history of the species benefits lab research. We also included what we see is the current major limitation of N. furzeri as a model animal – the lack of artificial standardised diet that would be consumed by adult fish where data from natural populations are crucial. We initially believed that this is outside of the scope of the “natural history” but we now see that lack of this important aspect would be misleading.

In addition, we expanded the section on gut microbiota where that link is very strong (subsection “Diet”) and highlighted the lack of knowledge on immune responses despite the turquoise killifish are faced with multitude of infections in nature and are capable to respond to them immunologically (subsection “Parasites”).

2) Despite the raising interest about N. furzeri by the scientific community, the reviewers felt it was an overstatement to refer to it as "an established vertebrate model in ageing research" and "the species of choice in […] evolutionary genomics, regenerative medicine, developmental biology and ecotoxicology". This text should be toned down. The revised text should aim to give a more balanced view (i.e. pros and cons) of how the natural history of the species contributes to its usefulness as a model organism. (Brief comparisons with other model organisms, including invertebrates and other vertebrates, could be considered to add wider context or strengthen arguments.)

We toned down those statements and refer to N. furzeri as "promising model in ageing" (Abstract) or "emerging model" (in some other disciplines).

"…become the species of choice…" has been replaced by "…become available for studies…"

We also pay more attention to compare the pros and cons of N. furzeri with other model animals, specifically highlighting "invertebrate-like" life history that is beneficial for laboratory breeding and vertebrate body plan (and this rationale is better explained in the current version of the manuscript).

3) Some of the cited work on killifish diapause and reproduction is from species besides N. furzeri; yet the way the references are cited does not make this clear to a reader unfamiliar with the system. Please include a 'disclaimer' somewhere in the text to indicate that what is known about diapause/development is drawn from studies of other related annual killifish, and although many aspects seem to be highly congruent among species, it remains to be determined whether the same applies to N. furzeri specifically.

Such disclaimer is now included in the main text ("Laboratory research in N. furzeri and other annual killifishes has suggested…"; "…diapause, at least in other killifish species, appears to be…") and in Box 1 ("While this developmental pathway appears strikingly congruent across all annual killifish clades (Furness et al., 2015b), it remains to be determined whether it also fully applies to N. furzeri.")

4) The main text mentions that little is known about the development in the wild. As such, please consider including at least one or two question about the developmental pathways of N. furzeri embryos in the wild into the "Outstanding questions" in Box 2.

That question is now included: "How do N. furzeri embryos develop under natural conditions? Current knowledge of the embryo development comes from laboratory conditions. As incubation in the lab largely differs from natural conditions, we need to know how much its diverges from the natural course of development."

5) The paper currently includes 60 references, 28 of which are directly from the two authors. Though the authors have majorly contributed to the development of N. furzeri as a biomedical and ecological system, they should consider if all these citations are needed and if other articles have been missed from the reference list.

We are aware of this unfortunate bias. This is primarily driven by the fact that we are indeed the only research group working on the ecology and evolution of wild populations of N. furzeri and this review specifically aims at the natural history of the species. We have tried to minimize that bias by including more reference to laboratory studies that investigated aspects of natural history of the species. There are now six new references from other teams added: Grégoir et al., 2017; Thoré et al., 2018, Woll and Podrabsky 2017, Dodzian et al., 2018, and Domiguez-Castanedo et al., 2013; Furness et al., 2015b), although we also added two relevant studies from our team that are highly relevant to the review (on thermoregulation and reproductive senescence in the wild).

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41548.009Article and author information

Author details

Funding

Grantová Agentura České Republiky (16-00291S)

- Martin Reichard

Grantová Agentura České Republiky (18-26284S)

- Matej Polačik

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Blažek, M. Vrtílek, J. Žák, V. Nezhybová and P. Vallo for support during our long-term research on wild killifish populations, R. Blažek, M. Vrtílek, J. Žák, C. Smith, A. Furness, D. R. Valenzano and an anonymous referee for constructive comments on the manuscript, and the Czech Science Foundation for financial support that has kept our killifish research ongoing through several successive projects awarded since 2006.

Publication history

- Received: August 30, 2018

- Accepted: December 11, 2018

- Version of Record published: January 8, 2019 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2019, Reichard and Polačik

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 5,810

- views

-

- 522

- downloads

-

- 42

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Ecology

Warming and precipitation anomalies affect terrestrial carbon balance partly through altering microbial eco-physiological processes (e.g., growth and death) in soil. However, little is known about how such processes responds to simultaneous regime shifts in temperature and precipitation. We used the 18O-water quantitative stable isotope probing approach to estimate bacterial growth in alpine meadow soils of the Tibetan Plateau after a decade of warming and altered precipitation manipulation. Our results showed that the growth of major taxa was suppressed by the single and combined effects of temperature and precipitation, eliciting 40–90% of growth reduction of whole community. The antagonistic interactions of warming and altered precipitation on population growth were common (~70% taxa), represented by the weak antagonistic interactions of warming and drought, and the neutralizing effects of warming and wet. The members in Solirubrobacter and Pseudonocardia genera had high growth rates under changed climate regimes. These results are important to understand and predict the soil microbial dynamics in alpine meadow ecosystems suffering from multiple climate change factors.

-

- Ecology

Over two decades ago, an intercropping strategy was developed that received critical acclaim for synergizing food security with ecosystem resilience in smallholder farming. The push–pull strategy reportedly suppresses lepidopteran pests in maize through a combination of a repellent intercrop (push), commonly Desmodium spp., and an attractive, border crop (pull). Key in the system is the intercrop’s constitutive release of volatile terpenoids that repel herbivores. However, the earlier described volatile terpenoids were not detectable in the headspace of Desmodium, and only minimally upon herbivory. This was independent of soil type, microbiome composition, and whether collections were made in the laboratory or in the field. Furthermore, in oviposition choice tests in a wind tunnel, maize with or without an odor background of Desmodium was equally attractive for the invasive pest Spodoptera frugiperda. In search of an alternative mechanism, we found that neonate larvae strongly preferred Desmodium over maize. However, their development stagnated and no larva survived. In addition, older larvae were frequently seen impaled and immobilized by the dense network of silica-fortified, non-glandular trichomes. Thus, our data suggest that Desmodium may act through intercepting and decimating dispersing larval offspring rather than adult deterrence. As a hallmark of sustainable pest control, maize–Desmodium push–pull intercropping has inspired countless efforts to emulate stimulo-deterrent diversion in other cropping systems. However, detailed knowledge of the actual mechanisms is required to rationally improve the strategy, and translate the concept to other cropping systems.